Chapter 3 – Literature Review

Few works deal explicitly with the four elements as an archetype of transformation in the sense developed in this work. The review of literature thus begins with the beginning of the first explicit elemental theories of the ancient Greeks, then briefly examines the four elements as a part of the alchemical tradition of the West. Modern re-inventions of elemental theory which have been put in to practice are then discussed before finally mentioning the works that have the most direct and significant bearing on the present study, which explicitly work towards an understanding of the archetypal nature of the elemental cycle and its relationship with consciousness and transformation.

The Greeks

There are a number of individuals who have taken the four elements and used them to explain, illuminate, or categorize various aspects of the world and our human experience of it, as well as of ourselves. In ancient Greece we find the first philosophers proposing individual elements to be the basic principle of the world:

Xenophanes (570-480 BCE): “All things come from the earth, and they reach their end by returning to the earth at last.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 33)

Thales (624-546 BCE): “The first principle and basic nature of all things is water.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 44)

Anaximenes (585-525 BCE): “As our souls, being air, hold us together, so breath and air embrace the entire universe.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 60)

Heraclitus (535-475 BCE): “There is exchange of all things for fire and of fire for all things, as there is of wares for gold and of gold for wares.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 71)

It later fell to Empedocles (490-430 BCE) to propose that not just not one single element but that each of these elements were fundamental principles, or “roots” of reality. He states that “Out of these, all things are formed and fitted together; it is by means of them that men think, suffer, and enjoy”, (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 137) and that “In reality there are only the basic elements, but interpenetrating one another they mix to such a degree that they assume different characteristics.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 130) Empedocles subscribed to the Eleatic idea that the real cannot either come into or go out of existence; thus all that is must be a consequence of an admixture of fundamental, unchanging elements. It was up to the dueling powers of Love and Strife to mold the elements into the ever-changing forms of the world.

Yet for Empedocles, the elements were not simply material in their nature, but arise from the power of the Gods: “Hear first the four roots of all things: shining Zeus, life-giving Hera, Aïdoneus [Hades], and Nestis [Persephone] who with her tears fills the springs from which mortals draw the water of life.” (Wheelwright, 1966 p. 128) Empedocles’ conception of the elements therefore included not just their material aspect, but their “spiritual essences (modes of spiritual being), which can manifest themselves in many ways in the material and spiritual worlds (they are form rather than content, structure rather than image).” (Opsopaus, 1998) Empedocles is therefore recognized as “a source for the major streams of Western mysticism and magic, including alchemy”, (Opsopaus, 1998) because it is just this type of thinking that is later refined by the alchemists.

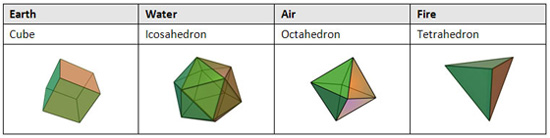

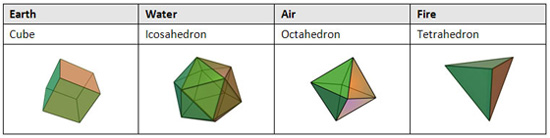

Plato took up the elements in his work Timaeus, relating them physically to what became known as the Platonic solids in his honor. In fact, we must credit Plato with first using the term elements for these principles of the world.

The word for element in its original Greek, stoicheia, has a root which means to proceed in order. This suggests an inner relationship between the forms which is the expression of a pattern. Each form was like an atom, or fundamental constituent of the material world, with the dodecahedron (the fifth and last Platonic solid) standing for the whole universe and therefore a ‘quintessence’ or fifth element. Plato, heavily influenced by the mystical Pythagorean school, indicated that because each of the forms could be broken into either 45-45-90 or 30-60-90 triangles, each form could be broken down and recombined with other triangles to form any of the solids. In other words, each element was capable of transforming into the others – an idea that is taken up much more directly through the experiments of the later alchemists.

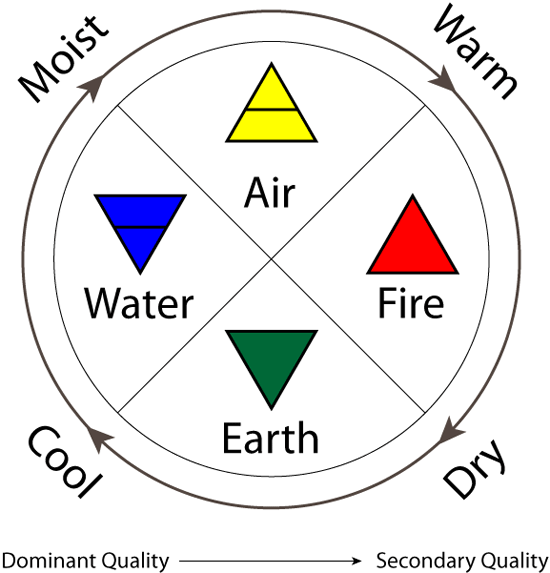

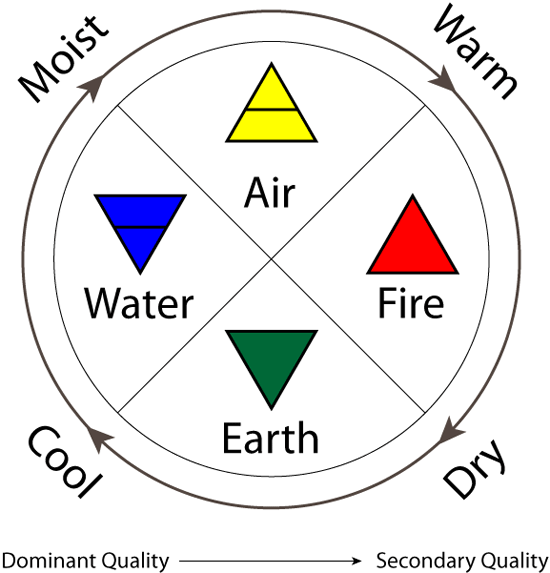

The mathematical-geometrical ideas of Plato were abandoned by Aristotle for a more qualitative approach. Rather than focusing on number, Aristotle used two sets of polarities to describe the primary nature of the four elements: cool-warm, and moist-dry.

Earth |

Water |

Air |

Fire |

Cool and Dry |

Cool and Moist |

Warm and Moist |

Warm and Dry |

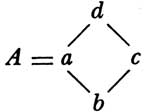

This relationship is better expressed in the following image, where we can see that the two diameters of the circle indicate the polarities that divide the four elements from each other. Additionally, the arrows indicate the dominant and secondary qualities of each element. For example, the element Earth is predominantly dry, and secondarily cool, while Water is primarily cool and secondarily moist, and so on.

These four qualities or ‘powers’, are considered to be more fundamental than the elements, and are thought to be the essences out of which the elements are formed. They can be seen over the course of the year in the seasons, and are therefore directly and intimately related to the processes of growth and decay, i.e. transformation of a cyclical nature. Growth begins in the spring under the influence of moisture, ascends to the warmth of summer, moves into the dryness of autumn, and descends into the coolness of the winter earth. This is the most obvious basis for considering that the elements manifest through an ordered, cyclic process, from Earth to Water to Air to Fire, and finally back to Earth.

Aristotle also recognized a fifth essence, the ‘quintessence’, calling it the aether, of which the heavens were made, but explicitly did not relate this to the last of the Platonic solids, the dodecahedron. The aether, according to Aristotle, was a substance completely different than the four ‘sublunary’ elements; it was incorruptible, unchanging, and eternal. It moved only in perfect spherical rotation (Decaen, 2004) and made up the heavenly bodies (the Moon was made of aether tainted by the four elements). Also called Idea, “Idea”, the fifth element was linked to decidedly non-material phenomena, and corresponds to the Hindu concept of “akasha”. The fifth element will be addressed directly in appendix A of this study.

Through Aristotle’s wide-ranging influence, the four elements became one of the foundational modes of understanding the manifest world. Galen (circa 129-200 CE), whose medical theories dominated Western medical science for over a millennium, took an important step in using the four elements as a basis for the four humors and the four temperaments. Aristotle’s experimental and practical approach pushed the more esoteric connections of the elements (such as Empedocles’ and Plato’s) underground. It took many centuries until the elements started to be understood again as more than just descriptions of the makeup of the material world. This shift occurred primarily within the alchemical tradition (with roots in Neoplatonism), where the elements started to be approached not just as descriptors, but as archetypes. Especially with the later alchemists, the elements became a way of speaking about intrinsic qualities not just of external substances, but also of psychological and spiritual states.

Later Alchemy

Greek alchemy was directly informed and inspired by earlier Egyptian wisdom, where the oldest alchemical texts originate (Bridges, 1999), and in its turn was taken up by Gnostic sects of early Christianity until their persecution by an organized, orthodox Church around the fourth century. This drove much of the Gnostic wisdom, alchemy included, underground, where it percolated until the rise of Islam and the rediscovery of the ancient Greeks by the Arab world. In the 8th century it underwent massive exposition and refinement in the minds of such thinkers as Jâbir ibn Hayyân (known as the ‘father of chemistry’, and from whose confusing documents the term ‘gibberish’ arose), Muhammad ibn Zakarîya Râzî, and Al-Tughrai, (whose translations of the oldest known alchemical texts of the Greek Zosimos, circa 300 C.E., were discovered in 1995), among others. It is through the Islamic scholars and seekers, and in particular the Sufi sects, that the ancient alchemical wisdom was preserved, refined, expanded, and given back to the West through the Knights Templar and others, where it sparked widespread cultural revival.

The alchemists are renowned for their deliberate obscurity and individualism of expression. Technical terms and phrases comprise the bulk of many alchemical works from the Middle Ages onward, reaching a height around the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe, where it became inextricably linked with the dilettantism of the ‘puffers’ and the search for easy money. Alchemists were generally a secretive lot – for two reasons. On the one hand, the Church considered many of the alchemical practices heretical and persecuted its practitioners, necessitating the need for secrecy. At the same time, the alchemists recognized that their work was not for everyone. It was recognized that alchemical processes, following the relationship between the microcosm and macrocosm, could not be undertaken successfully if done purely as operations on material nature. Rather, the moral capacity of the alchemist, as well as the alchemist’s overall character and development, necessarily played a role in the success of the sensitive alchemical operations. Being prepared for the knowledge in this way was a crucial element of success. To this end, alchemists would usually only transmit the greatest secrets of their art orally to trustworthy individuals, and when they set down their doctrines in text, their tactics to keep the information accessible to only the most sincere seekers included omitting or obscuring information with vague hints or purposefully neglecting to include crucial aspects of the process (often with some sort of appeal that the adept would surely discover the appropriate next steps with concerted effort), providing deliberate misinformation, or encoding of secrets in codes or in the form of seemingly abstract images and technically obscure language. This had the dual effect of safeguarding their knowledge from the uninitiated while preventing the Church from discovering the true teachings and any potential grounds for persecution.

Despite the obscurity of many alchemical writings, some trends can be discerned. In particular, throughout Western and Islamic alchemy, the four elements played a primary role as manifestations of the prima materia, an Aristotelian term that refers to the primal essence out of which the philosopher’s stone was to be formed. Alchemists worked with the four elements both in their manifestation as the various forms of physical matter, but also esoterically as the physical carriers of the divine potential of transformation, the result of which appears physically in the element of gold and spiritually as the ‘alchemical marriage’ of the diverse parts of the alchemists body, soul, and spirit.

Yet even in the alchemical tradition, the elements were not explicitly developed into a tool for the analysis of transformation in isolation. The alchemical literature contains an extremely wide variety of descriptions, indications, and usages of the elements. In fact, each element can have multiple forms or manifestations (different kinds of fire or water, for example) (Jung, 1970 p. 184). They were seen by many alchemists as the central players in the various processes. The 13th century Italian monk and alchemist Ferrarius even defines alchemy as “the science of the Four Elements, which are to be found in all created substances but are not of the vulgar kind. The whole practice of the art is simply the conversion of these Elements into one another.” (Quoted in Klossowski de Rola, 1973) The role the elements played, however, was generally in service of the larger drama of the “Great Work” – the search for the philosopher’s stone and the self-purification of the alchemist’s soul.

As this study is not intended to be of the elements in alchemy proper via its personages and historical texts, a detailed review of the role of the elements, which could easily fill multiple volumes, will be avoided. For the purposes of the present study, alchemy stands as an inspirative body of work from which many insights are taken and developed, but independently and in a way according to the outlined methodology. Therefore, a large portion of the proposed study will require the refinement of the theory of the four elements into one that directly and explicitly addresses the central theme of transformation.

Jacques Vallee

Jacques Vallee, in his book The Four Elements of Financial Alchemy (Vallee, 2000), explicitly uses the four elements as a template for individuals to use when planning their finances. He uses the elements in a straightforward, classificatory way, identifying investment categories according to their level of risk and volatility. Interestingly, Vallee states that he “came to recognize four major categories of risk and reward, because they triggered four distinct emotions” within him. (Vallee, 2000 p. 14) In other words, it appears that even if the elements are “only a metaphor” (Vallee, 2000 p. 14), their usefulness arises out of the way in which they can be related to states of human consciousness – in this case the variety of emotional states arising around monetary concerns. With this background, Vallee is then able to trace his emotional responses back to the types of investments that triggered his particular ‘elemental’ responses. What is useful to point out here is that the process involves not just a recognition of a state of consciousness, but that once this state has been recognized, it can be projected back out onto the world as a lens that helps bring to focus patterns that may otherwise be unrecognized. In other words, he uses the overt qualities of each element as a way to make sense of all the potential types of investments by finding qualitatively similarities; T-bills are an Earth investment because they are virtually risk-free and backed by the United States government, whereas stocks in individual companies are a Fire investment, carrying a much higher risk of fluctuation and no guarantees of any sort, but with potentially large returns. In Vallee’s work, the elements themselves, let alone their philosophical underpinnings, are never addressed. Yet his work demonstrates that even without an obvious understanding of the intricacies of the elemental cycle, its application can be both straightforward and fruitful.

Heather Ash

Heather Ash, a student of Toltec wisdom, shows how the four elements can be “used as guideposts of transformation” in her book The Four Elements of Change (Ash, 2004). Here, she describes how each element represents a different body of the human being: Earth --> Physical body, Water --> Emotional Body, Air --> Mental Body, and Fire --> Energetic Body. Ash’s primary approach could be termed psychological. She briefly describes each element, relating them to the seasons and to a few basic qualities which double as psychological descriptors. For example, Fire corresponds to the season of Summer, of “blossoming and tremendous energy” in which “any thoughts or inspirations need to be energized. This is a time for action.” (Ash, 2004 p. 22) Although more philosophically cognizant than Vallee’s work, Ash focuses on stories of personal transformation and practical techniques for working through psychological challenges. In particular she relates each element to a different capacity or “art”, which – if mastered and integrated with each of the other capacities – can help create a strong, fluid, adaptable, and effective personality, a “master of balanced change” (Ash, 2004 p. 19). These four capacities are as follows: Earth --> the art of Nourishing, Water --> the art of Opening, Air --> the art of Clear Perception, and Fire --> the art of Cleaning. The structure of the book, and her overall presentation, places the elements in the order Air, Fire, Water, and Earth, suggesting some recognition of a deeper patterning at work between the elements, but does little to justify this choice. She does state that “We begin with air, but working with the four elements is not a linear process. The elements and their actions blend and support one another to create [a] container for change.” (Ash, 2004 p. 43) The present study attempts to show that while on the one hand this sentiment is quite accurate, in-depth analysis shows that the elements present themselves via a fractally based cyclicality which is implicitly ordered.

Deborah Lipp

Deborah Lipp, a high priestess in the Pagan tradition, has done extensive work with the four elements, summarized in her book The Way of Four. (Lipp, 2004) She takes a very practical approach to the four elements, utilizing them as a classificatory scheme that she applies to the natural world, personal psychology, home life, attire, dating, work, ritual, and meditation, among other arenas. In her first chapter she explores the history and background to the four elements, and states that “Everything that is whole contains all four [elements], and can be understood more deeply by dividing it into four and viewing it through that lens.” (Lipp, 2004 p. 3) This characterizes her overall approach to the elements very well; she divides the various fields mentioned above into four categories, and analyzes the results from the perspective of each individual element. She consistently emphasizes the need for balance between the elements in any given arena, and to accomplish this she generally recommends identifying the unbalanced element and then working to recognize and bring into play its opposing element. According to the elemental cycle as discussed in this study, this would essentially be an Air approach to balance, in which the polar element is brought in for its complementary aspect.

Although Lipp’s work is excellent at identifying elemental aspects of various parts of daily life, there is little phenomenological and philosophical background or justification beyond the more or less overt sympathetic relationships found when the qualities of each element show up in some new domain. The ‘law of sympathy’ is very powerful, but Lipp rarely moves beyond the most obvious level of sympathetic relation, giving the work a somewhat superficial feel. This may be by design in order to reach a larger audience, as the book is interspersed with many practical workbook-type questionnaires that help readers type themselves in various areas according to the elements, as well as including many practical exercises to work with each element (although often in a fairly superficial way).

From the perspective of the present study, what Lipp is most obviously lacking is an integrated theory and practice concerning the elements which includes not just the individual elemental qualities, but coherently relates each element to the others in a unified whole. Practically speaking, such an approach would be more flexible and potentially useful both in a wider variety of situations, while – more importantly – providing a structured avenue for a deeper and more integrated exploration of a given issue or topic to which the elemental cycle could be applied. For example, rather than, as suggested by Lipp’s approach, balancing an overabundance of Water by adding Fire aspects, it may be more useful to balance an overabundance of Water by showing how Water can lawfully transform through Air into Fire – an approach more cognizant of Aristotle’s recognition of the antagonistic nature of the elemental opposites.

TetraMap

Jon and Yoshimi Brett have taken the four elements as a basis for developing a tool for understanding and engendering healthy communication in the business world. They place the four elements on the four faces of a tetrahedron, which unfolds into a map (their business, TetraMap derives from this form). In this scheme, the elements have the following major qualities: Earth – firm, Water – calm, Air – clear, and Fire – bright, which are seen as metaphors for a holistic basis upon which healthy transformation can grow. (Y. Brett, personal communication, March, 2007) To quote from their website:

TetraMap and its user-friendly workbooks and Leader Guides take learners on journeys that reflect our potential to consistently add value - individually, as teams, and as whole organizations. The strategy is long-term, and uses TetraMap as a guide through broader organizational issues involving diversity, human capital and business development. (Brett, 2008)

Additionally, in the workplace the elements work according to the following relations:

Earth |

Water |

Air |

Fire |

Goals |

Values |

Rules |

Spirit |

Direction |

Unity |

Reason |

Motivation |

Healthy Competition |

Healthy Morale |

Healthy Feedback |

Healthy Fun |

The Bretts find that the four elements, found everywhere in nature, provide a very basic and rich common ground from which many levels of transformation can be addressed. They explicitly recognize that the four elements are not capable of transformative effects in isolation, but together work as a whole, metaphorically found in the tetrahedron. This form demonstrates the qualities of the elements when taken as a unity: each side requires all the others for its stability (which is remarkable – Plato felt that tetrahedrons were the geometrical foundation of the physical world), and no face opposes any other face directly, but all work together with mutual complementarity.

The work of TetraMap closely parallels some of the outcomes indicated by the present study, which show much promise for applications of the elements to psychological self-understanding, dialogue work, and corporate leadership. Although within TetraMap the four elements necessarily form a unity, the Bretts do not overtly utilize the sequential patterning from Earth to Water to Air to Fire that is found by the present study to be both implicit in the elements and central for a complete understanding of how they work together.

At the same time, the Bretts are very clear about the distinction that the map and the territory are different, and that the TetraMap is “just a map”. This is quite true from an introductory perspective, which utilizes the elements as signs; the present study attempts to show how the elements can engender a consciousness in which the map and territory actually merge together in an experience that bridges the normal inner-outer boundary.

The fact that even a basic application of the four elements can yield a useful and successful corporate and group counseling model attests to the element’s inherent potential as both a language of and facilitator for change.

Carl Jung

C.G. Jung’s contributions to the study of alchemy in the modern era are wide-ranging and difficult to comprehend, but particularly bring out the symbolic and psychological aspects according to his own theories concerning the unconscious mind. Jung notes the power of four-fold arrangement:

The quaternity is an organizing schema par excellence, something like the crossed threads of a telescope. It is a system of coordinates that is used almost instinctively for dividing up and arranging a chaotic multiplicity, as when we divide up the visible surface of the earth, the course of the year, or a collection of individuals into groups, the phases of the moon, the temperaments, elements, alchemical colours, and so on. (Jung, 1978 p. 242)

Jung does not explicitly expound upon the doctrine of the four elements in and of itself. Rather, he shows how it forms an echo of the patterns inherent in the symbolism of the Gnostics and of its continuation in alchemy. He does, however, explicitly recognize that the four elements form a rota or wheel, which acts as a mandala. Mandalas, for Jung, are almost invariably symbols for the archetype of wholeness, which he calls the self.

The most important of these [symbols] are geometric structures containing elements of the circle and quaternity; namely, circular and spherical forms on the one hand, which can be represented either purely geometrically or as objects; and, on the other hand, quadratic figures divided into four or in the form of a cross. (Jung, 1978 p. 223)

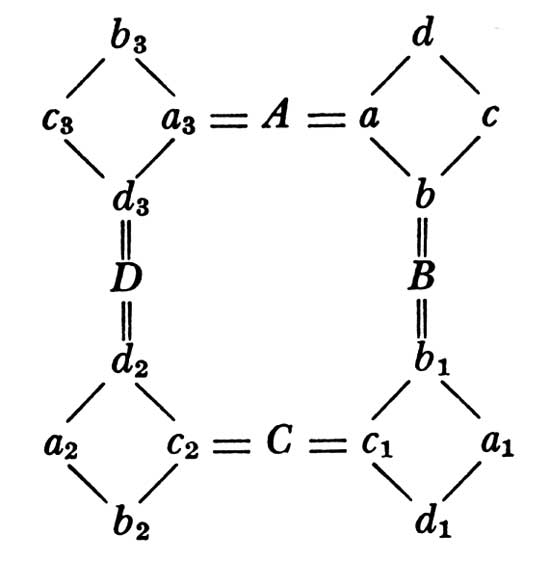

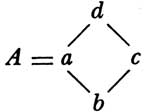

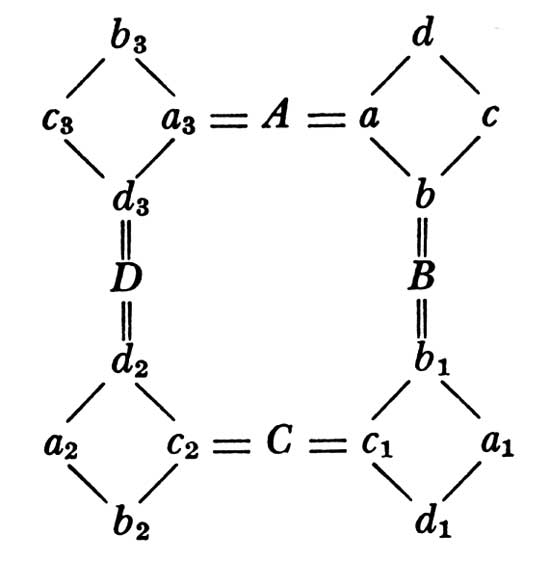

The most interesting and directly related aspect of Jung’s work with the quaternary archetype concerns its formulation as an equation. “With regard to the construction of the formula, we must bear in mind that we are concerned with the continual process of transformation of one and the same substance.” (Jung, 1978 p. 257) He arranges his equation spatially in mandalic form:

As Jung points out, this formula “reproduces exactly the essential features of the symbolic process of transformation.” (Jung, 1978 p. 259) It embodies the rotational movement from one phase to the next in an ordered and cyclical fashion which Jung points out occurs “by a kind of enantiodromia.” (Jung, 1978 p. 258) It includes as well

the antithetical play of complementary (or compensatory) processes, then the apocatastasis, i.e. the restoration of an original state of wholeness, which the alchemists expressed through the  symbol of the uroboros, and finally the formula repeats the ancient alchemical tetrameria, which is implicit in the fourfold structure of unity:

symbol of the uroboros, and finally the formula repeats the ancient alchemical tetrameria, which is implicit in the fourfold structure of unity:

What the formula can only hint at, however, is the higher plane that is reached through the process of transformation and integration. (Jung, 1978 p. 259)

Jung’s diagram is nearly identical to the mandala used to express the elemental cycle in the present study (see page 79 of this work) which can indeed be seen as symbolically equivalent of the uroboros. Jung’s formula makes explicit some of its major qualitative aspects, particularly the recurrence of the basic pattern as an element of itself – i.e. is self-similarity. Interestingly, Jung also mentions that the transformative re-working of the “totality into four parts four times, means nothing less than its becoming conscious.” (Jung, 1978 p. 259) This astonishing statement, like many of the gems of wisdom to be found in Jung’s works, remains essentially unexplained, but the present work provides a detailed foundation that naturally shows how this can be the case.

Jochen Bockemühl

Jochen Bockemühl, a biologist and student of Rudolf Steiner’s Spiritual Science, considers the elements as modes of observation, that is to say, as modes of human consciousness. Bockemühl, like so many others who are familiar with Goethean phenomenology, develops the elements in this way through the example of observing plants. His concise and insightful work presents a number of conclusions that support the present study, both in terms of method and content, for example by noting that the “division of the sense world into different ‘layers’, [the four elements] experienced at first purely outwardly, can, when we look inwardly, make us aware of the different layers of our thinking.” (Bockemühl, 1985 p. 5)

The Earth mode of cognition gives us the impression that “we come to firm conclusions, that we are always limited to the surface of things and see them as separate, exactly because the qualities of solidity, impenetrability and separateness are rooted in our cognitional attitude itself.” (Bockemühl, 1985 p. 9) The Water mode of cognition, which we “employ continually, but most often in a dreamlike way”, (Bockemühl, 1985 p. 11) leads beneath the initial surface impressions to deeper underlying processes, which are always fluid and in motion. In the air mode we are able to contact the gesture of the phenomenon by opening ourselves to its subtle characteristics by “offering the image the opportunity to appear and to speak.” (Bockemühl, 1985 p. 25) The fire element is most difficult to characterize, but yields a mode in which we “feel ourselves united with [the] energizing activity” (Bockemühl, 1985 p. 36) of a phenomenon – we perceive it almost as if were ourselves stood in the place of the phenomenon as a subject.

Bockemühl’s admirable presentation of the four elements as observational modes [Betrachtungsweisen] is given primarily through a discussion of plant observation, but as the work is introductory in nature he does not explicitly generalize his understanding to alternate circumstances, although that this could be done is clear. He does not appear to view the elements as forming a cyclical pattern, addressing them instead in a more directly hierarchical manner. However, Bockemühl’s research directly parallels the aims of the present study (likely because of his anthroposophical background) and gives an alternate and complementary way into looking at the four elements.

Nigel Hoffmann

Nigel Hoffmann, similarly inspired by Rudolf Steiner and anthroposophy, explicitly connects the four elements to the Goethean methodology: “The Elements are a way of understanding and entering into the different ‘dispositions of thinking’ which belong to Goethe’s way of science.” (Hoffmann, 2007 p. 22) He connects the four elemental modes of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire to the mechanical, sculptural, musical, and poetical; each of these represents a unique and complementary way of dealing with phenomena. These capacities are both active and passive – being both a frame of mind and a way to interact with the world.

Hoffmann devotes a good portion of his book, Goethe’s Science of Living Form to explicating each element and its corresponding qualities. The underlying philosophy is addressed through connection with three ‘higher’ capacities of knowing elucidated by Rudolf Steiner, called Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition (written with capitals to distinguish them from their more common meanings), and the phenomenological work that Goethe accomplished and which has direct implications for the way science is done today. Hoffmann, in recognition that “to properly understand what is meant by the Elemental modes of cognition one must literally do them”, (Hoffmann, 2007 p. 71) then fruitfully applies his understanding to the Yabby Ponds area north of Syndey, Australia, in an attempt to elucidate and demonstrate how the elemental modes inform a Goethean study of place. If any reader is unsatisfied by the present study, Hoffmann’s book would be the first stop for a complementary approach to the topic at hand. Like Bockemühl, Hoffmann does not explicitly address the elements as a cycle or mandala, nor is the breadth of the elemental approach explored. In particular, it seems that the most amenable way in which the elemental modes are broach is through (in the Goethean vein) a study of plant life. Although there is a certain logic to this pattern – if most of the time our modern culture calls upon an mineral-based mode of thinking, then using an example from the next-higher kingdom of the plants would be a sensible next step – the present study aims to universalize the elemental modes to the extent to which that is possible; this requires application to as wide a variety of phenomena – not just ‘natural’ – as possible. For help in this endeavor, we must turn to the work of Dennis Klocek.

Dennis Klocek

The most directly significant modern works that deal specifically with the alchemical elements of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire with respect to their mandalic, cyclical nature and relationship to transformation are those of Dennis Klocek. My own approach is therefore heavily influenced by his works, Seeking Spirit Vision (Klocek, 1998), The Seer’s Handbook (Klocek, 2005), and particularly the Consciousness Studies Program (formerly called Goethean Studies) he directs at the Rudolf Steiner College, which I had the great fortune to attend twice. He expressed the basic premise for this study succinctly: “These four stages [of the elements] are an archetypal pattern underlying most interactions between humans as well as most patterns of change in the natural world.” (Klocek, 1998).

For the most part, the elemental cycle is used by Klocek in terms of its esoteric, symbolic relationship to stages of the transformation of the human soul. He clearly identifies the four alchemical elements as forming a continuous cycle, and works with the qualities of each element particularly with respect to how they form analogues to states of consciousness. This study builds upon much of the foundation laid by Klocek, but is more focused on providing an in-depth look at the elemental mandala as a phenomenon in its own right. Because Klocek’s work with the elements is deeply interwoven with a number of other specific concepts from various disciplines, it is difficult to extract directly from his works information about the elemental cycle so that it stands on its own. The present study is party an attempt to do just this, so that its nature, usage, and boundaries can be understood in what hopefully will be a direct and clear manner. Although Klocek works deeply with the alchemical mandala, its development is secondary to his more fundamental goal of providing context and help to those wishing to undertake the work of self-transformation. Klocek’s work has many fruits (see Chapter 5: Areas of Potential) – this study is the outcome of the tending of only one of the seeds.

Rudolf Steiner

It is important to mention that Klocek’s work, the methodological approach of Goethean phenomenology (and its corresponding epistemology) used in this study, the works of Bockemühl and Hoffmann, and this study itself, are deeply inspired by the work of Rudolf Steiner. Steiner, a difficult to classify scientist, educator, and spiritual researcher of the early 20th century, provides the underlying context and foundation for my interest in the topic. Steiner spoke and wrote much about the elements and their nature, but primarily from an esoteric standpoint and not in the specific formulation that will be addressed in this paper. Yet much of Steiner’s insights are modern developments of alchemical principles. Those readers who are familiar with Steiner’s works might read much ‘between the lines’ of the present work, which may be seen as a continuation of impulses whose foundation was laid by Steiner’s work in bridging through clarity of thought and depth of perception the seeming split between the world of the spirit and the world of the senses.

symbol of the uroboros, and finally the formula repeats the ancient alchemical tetrameria, which is implicit in the fourfold structure of unity:

symbol of the uroboros, and finally the formula repeats the ancient alchemical tetrameria, which is implicit in the fourfold structure of unity: