Patterns in Process:

Transdisciplinarity as a Background for Working with an Archetype of Transformation

By Seth Miller

March 15, 2009

Abstract

This essay explores the topic of my potential dissertation inquiry by situating it within the framework of transdisciplinarity. A number of questions are addressed: 1) the nature and importance of my topic, 2) examination of resources and the dominant disciplinary discourse connected with my topic, 3) how my topic might be framed from a cybernetic/complex approach, 4) a critical examination of my assumptions, beliefs, and position with regards to my topic, and 5) the extent to which my topic leads me along a process of creative inquiry.

How often do we find ourselves in a position of not being able to see something unless it is first pointed out to us? This happens all the time with the visual and other physical senses, but of course also occurs in our thinking; certain concepts seem to hide in plain sight, and unless we are cued into where and how to look for (or to think about) them, they slide on by as a part of the undifferentiated background of conceptual life. Usually we are introduced to these sorts of concepts just like we are to new people, through a third party who is already familiar with each of us: “Seth, I’d like you to meet Recursion; Recursion, this is Seth.” Often with this sort of introduction comes an experience: “Oh hello Recursion! You know, I feel like you must hang out at some of the same coffee-shops as I do, but we’ve never been formally introduced.” And so a relationship begins with a concept, and just as with human beings, you can become more intimate and familiar, get into fights, seek new levels of understanding, and go on adventures.

I was introduced to the topic of my inquiry 10 years ago: an archetypal pattern of the process of transformation, situated in the four alchemical elements of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, and we have been journeying together ever since. This pattern seemed like the kind of concept (although archetypes are much more than merely conceptual) that Goethe called an “open secret”—invisible to cursory examination, but completely out in the open and obvious once you know how to recognize it, and have some familiarity with its style.

Phrased more simply, my inquiry concerns how transformation occurs. Specifically, I’m interested in the extent to which there are lawful patterns that describe how transformation really happens in the world, both in personal experience of one’s own transformation and as a way of describing more ‘objective’ processes that do not explicitly have to do with humans. Are there patterns to transformation, or does transformation occur through a wide variety of processes which have little or no relationship to each other? How do we know that transformation is occurring, or has occurred?

My feeling about this can be made clear through a metaphor. There are many paths up a mountain, and if you ask each person to describe the specific details that they observed on their way, you’ll get a unique description from each person. This is complicated by the fact that even if two people travel the very same path, they will likely pay attention to different features and give diverse accounts. Nevertheless, with some probing you can find certain aspects which begin to coincide and link from story to story; for example, the fact that no matter what path you take, an overall directionality is apparent: from low to high elevation. Other patterns exist, but this serves to illustrate the point that even though “transformation” can happen in an extremely wide variety of contexts and through a number of seemingly diverse processes, it is my understanding that certain patterns continually inform how transformation unfolds. In particular, my research has brought me to an understanding of some of these patterns, which, borrowing from the language and tradition of alchemy (where everything is about transformation) I call Earth, Water, Air and Fire. These four elements are manifestations of the archetype of the pattern of transformation. Each element describes one qualitative stage of the process through which any transforming situation unfolds, and they fit together in a cycle (or rather, a vortex, which is always a spiral), moving from an initial (often unconscious) Fire, onwards to Earth to Water to Air, then to Fire again, and back to what we could call a New Earth. The details of each elemental stage and the building up of the underlying theory was the subject of my master’s thesis 1.

My present inquiry revolves around the exploration and application of this archetypal metaphor to human transformation. Central to my inquiry is simply the desire to become more familiar and fluent with how the pattern works, where it works (and where it doesn’t), and the extent to which consciousness of the pattern can be of practical help in regards to work that attempts to bring about, make efficient, or to simply understand transformative processes. The elemental cycle has clear potential applications in therapy, counseling, spiritual practice, dialogue and communication, planning, management, education, personal growth, and scientific realms; as an archetype it necessarily crosses boundaries such as these with ease. The linking factors between all these areas are processes in human consciousness. As there is almost no published literature that deals with this particular way of dealing with the elements and transformation, my work will be primarily to remedy this gap, and to make the strongest case for the applicability of the elemental cycle through specific examination of transformative situations.

I believe this work is important for a number of reasons. My experience with the elemental cycle has shown me that it can be a reliable guide for the deepening of consciousness around transformative processes. It helps clarify and complexify understanding, it responds flexibly to a variety of situations and can be applied across scales, and it actively helps lead one through transformations by providing contact with and context within an archetypal, lawful, process that transcends the potentially limiting and blinding nature of personal (subjective) patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving. This kind of understanding and approach to transformation, which has transpersonal roots and implications, and which builds on a view of the human being and cosmos that is normally ignored by the majority of academic discourse (as it lies outside any academic discipline), is simply missing in the literature. By studying the application of the elemental cycle, and framing it through the more modern languages of transdisciplinarity, complexity theory, cybernetics, and general systems theory, I hope to provide a strong foundation for its theoretical basis and practical potential. Ultimately, I aim at bringing to a larger audience an entryway into a different way of thinking and perceiving, which can adaptively move between self and other, operates fluidly on multiple levels, includes the full complexity of the human being, and which recognizes and employs the transpersonal. This way of thinking is compatible with the three principles underlying the paradigm of complexity laid out by Edgar Morin (2008): 1) the dialogic, which “allows us to maintain duality at the heart of unity, [associating] two terms that are at the same time complementary and antagonistic” (Morin, 2008, p. 49), 2) organizational recursion, where “the products and the effects are at the same time causes and producers of what produces them” (Morin, 2008, p. 49), and 3) the holographic principle, where “the part [is] in the whole, [and] the whole is in the part” (Morin, 2008, p. 50).

This inquiry has always presented me with a number of difficulties (but many more successes and insights), many of which are brought to a head when thinking about this topic as the basis for my PhD dissertation. First of all, what I’m after is very, very difficult to work with directly, because of its intrinsically wily nature. Archetypes cannot be pinned down and captured like a butterfly on an etymologist’s display board. You can’t even capture transformation by pinning down each successive stage of the caterpillar-to-butterfly process; you only end up with the death of the very thing under scrutiny (this is a manifestation of an Earth-type approach to transformation). Working with an archetype–particularly an archetype of transformation–requires a different way of working. (A treatment of what I mean by the word archetype follows the discussion of Jung below.)

Transdisciplinarity, luckily, has run into and attempted to deal with many of the very same problems that I face in my inquiry. Basarab Nicolescu, one of the founders of transdisciplinarity, points out that disciplinary processes of knowledge creation—the dominant mode through which most knowledge in the Western world has been constructed for the past few centuries—is only one arrow shot from the bow of knowledge (Nicolescu, 2008, p. 3), the others are multi-disciplinarity, inter-disciplinarity, and finally transdisciplinarity.

Disciplines have a tendency to form specialized knowledge on the basis of assumptions and methodologies which are unique to the individual discipline. Indeed, many disciplines are initially formed in and by the very process of distinguishing themselves from other disciplines in just this way. While allowing for extremely specialized forms of knowledge, such disciplinarity can lead practitioners into the situation, described by Brue Wilshire (1990), in which “missing is any sense that anything is missing” (Wilshire, 1990, p. 12).

Disciplines keep their purity by engaging in what Wilshire calls veiled purification rituals: “the refusal to mix a stance with other views (and evidence) which are palpably relevant to it. Mary Daly calls it methodolotry. Each field’s formalism defines and guards its boundaries” (Wilshire, 1990, p. 161). Lewis Gordon (2006) identifies a similar pattern:

The emergence of disciplines has often led to the forgetting of their impetus in living human subjects and their crucial role in both the maintenance and transformation of knowledge-producing practices. The results are special kinds of decadence. One such kind is disciplinary decadence. Disciplinary decadence is the ontologizing or reification of a discipline.” (Gordon, 2006, p. 4)

Transdisciplinarity attempts to address this reification and lack of self-reflectivity by explicitly including the inquirer into the inquiry (Montuori, In Press). Alfonso Montuori, a creativity researcher and professor at the California Institute of Integral Studies, points out that this involves not simply inserting the subject into the topic, but rather evolves through recursive relationship between the subject and the topic: “in order to understand the world we must understand ourselves, and in order to understand ourselves we must understand the world” (Montuori, In Press). By purposefully and critically inserting the inquirer back into the inquiry, we are continually called to recognize that real human beings, with all our thick complexity, are the source of inquiry, and that inquiry purged of its living source tends to become both abstract and overly-reified, ossifying both itself and the discipline which supplies its formalism. As Nicolescu (2008) indicates, “knowledge is neither exterior or interior: it is simultaneously exterior and interior” (Nicolescu, 2008, p. 9, original italics)

Critically placing the self-reflexive inquirer into the inquiry process thus means that transdisciplinarity attempts to bring to light fundamental assumptions about how knowledge is constructed around the inquiry topic. In this sense, a transdisciplinary approach includes an examination not just of one’s own assumptions about the inquiry, but also the assumptions made by the dominant disciplines in which the topic is addressed, in an effort to allow the inquiry topic itself to lead the way, rather than the self-segmented and reified modes of knowledge construction adopted (or forced) by each individual discipline.

Of course, in order to examine these assumptions, the dominant disciplinary discourse (DDD) must be identified, along with its major players. In the case of my own topic of inquiry, there is very little written work that deals with the elemental cycle, let alone how the elemental cycle works in a specific way with regards to transformation. The topic itself has, obviously, deep roots in the alchemical tradition, where multiple approaches and understandings of the elements are manifest, stretching all the way back to Aristotle, Empedocles, and beyond (at the very least, the topic has some real history!), but most of this discourse is either historical in nature, esoteric, or simply dated. On top of this, the vast bulk of the alchemical works do not deal directly with the elemental cycle in the way that I am interested in developing it: as a formative pattern that describes a lawful process of transformation. This kind of understanding, as far as I can trace it, finds its modern roots in the work of Rudolf Steiner, whose detailed cosmology and description of human and spiritual worlds implicitly describes the relationship of the four elements as a basis for transformative processes. However, this aspect of his work was by no means central; the stages of the four elements serve less as a directly addressed content than as an oft-used structural container for his insights.

Nevertheless, some modern works on alchemy do provide a picture of the kind of style of thinking that makes the elemental cycle intelligible. Specifically, this is a way of thinking that meshes very well with a transdisciplinary approach, in that it embodies the “three postulates” of transdisciplinarity, as formulated by Nicolescu (2008):

- There are, in Nature and in our knowledge of Nature, different levels of Reality and, correspondingly, different levels of perception.

- The passage from one level of Reality to another is insured by the logic of the included middle.

- The structure of the totality of the levels of Reality or perception is a complex structure: every level is what it is because all the levels exist at the same time. (Nicolescu, 2008, p. 10)

That alchemy includes these postulates in its experimental and epistemological foundation is a topic for another day; the important thing to consider is that these assumptions are present in the main tradition in which my inquiry has a home.

More recently, I have been inspired by the work of Dennis Klocek, who initially introduced me to the transformative capacity of the elemental cycle in a seven-month long course called “Goethean Studies”. His books Seeking Spirit Vision, and The Seer’s Handbook (Klocek, 1998, 2005) do contain discussion about the elements, but the elemental cycle itself isn’t a major component. Nevertheless, Klocek is one of, if not the, major authority on the elemental cycle, and has been working with it for over 30 years. Also of note is Jochen Bockemühl, a biologist and student of Rudolf Steiner’s Spiritual Science, who considers the elements as modes of observation, that is to say, as modes of human consciousness (Bockemühl, 1985). This is directly in line with my approach to the topic, although he doesn’t explicitly generalize the theory or work with the elements as a cycle. The last major resource that deals with the elements in an analogous way is Nigel Hoffman (2007), who similarly connects the elements to ways of thinking: “The Elements are a way of understanding and entering into the different ‘dispositions of thinking’ which belong to Goethe’s way of science.” (Hoffmann, 2007, p. 22) In his book, Goethe’s Science of Living Form, Hoffman applies the different modes of thinking in a Goethean-style consideration of the Yabby Ponds area north of Sydney, Australia. However, like almost all others who have dealt with the four elements (except Klocek), Hoffman doesn’t explicitly deal with their cyclical nature, and doesn’t explicitly generalize with respect to how the elements work in regards to understanding transformation.

My own approach is aligned with the above authors, and I consider it to be an extension of Klocek’s work. The fact that the above authors (as well as I) identify as an inspiring source the works of Rudolf Steiner means that a number of assumptions are made that inform a background to the topic of transformation. Most importantly is the assumption that transformation is never an isolated event, but is contextually embedded both in physical processes as well as spiritual processes. Direct understanding and work with the context(s) of transformation is necessary, because the context is both epistemologically and ontologically significant. Additionally, it is assumed that the physical and spiritual processes do not have a dual, Cartesian-type relation, but are co-incident and co-evolutionary; they are mutually reinforcing and creating, even co-constitutive. The ‘outside’ world, therefore, is not treated in a reductionist, ‘objective’ way (characterized by Morin as “simple thought” (Morin, 2008, p. 4)), because it is understood that the outside and inside are directly linked. Neither is it treated in a purely subjective way; it is assumed that through specific processes, human beings can learn how to be aware of the extent to which personal attributes and epistemological habits color one’s perception; this opens up the possibility of new ways of perceiving and thinking that don’t rely so much on what is given as what is possible.

With regards to my inquiry topic, I assume that something of the essential nature of what it means—of what it is—to be human centers on our capacity for transformation: we are beings built for the creative embodiment of transformation. I assume that transformation doesn’t happen arbitrarily, randomly, or nonsensically (despite how it may seem at times) and that there is good reason to believe that patterns which structure and inform transformative processes can be conceptualized and utilized. I assume that processes which do flow with these patterns in a lawful way will produce effects and transformations which will be qualitatively and significantly different (more coherently connected to lived experience and contextual meaning, longer lasting, leading to greater involvement with self and others and leading to even further transformations, etc.) than processes which do not flow with the patterns. A more basic assumption, implicitly mentioned above, is that transformation always touches the spiritual in the human being, and thus a consideration of spiritual context and processes is both useful and important if we wish to deal with the resolute complexity of transformation, avoiding the various critiques of Gordon, Montuori, Morin, Nicolescu, and Wilshire.

There appear to be no scholarly journals which have dealt with this topic. Therefore, I have had to cast a wider net to find related works. Generally speaking, my topic concerns the process or stages of transformation; the academic area with the greatest number of publications on this theme is psychology, although there are some related articles in journals dealing with education, management, philosophy, anthropology, and religion. Within psychology, the most relevant literature comes from the realm of depth psychology, which, linked to Jung, includes a non-trivial understanding of alchemy as an ongoing thematic reference.

A general survey of the available literature shows that transformation has been identified as occurring primarily in and through very specific contexts:

- dealing with addiction (alcohol, smoking, eating)

- suffering, illness, loss, near death experiences, and/or trauma

- existential crises

- psychotherapy and/or group work

- spiritual and/or meditative practices

- education and/or adult learning and self improvement

- political action

- parenting (and other life-transitions)

Most articles and dissertations deal with only one area of transformation, and make only very limited claims with regards to application in diverse situations. Some mention stages of transformation; almost all are qualitative, with the major methodologies spanning grounded theory, phenomenology, heuristics, and some narrative analysis, along with theoretical or reflective works.

With regards to stages of transformation, much foundational work has been done by Arnold van Gennep (Gennep, 1960), who identified three stages in ritual transformation: preliminal, liminal, and postliminal. Following Gennep, Victor Turner kept the three-stage model (separation, liminal, reaggregation) but focused on the liminal stage (Turner, 1969). Joseph Campbell was influenced by these models and used them as the basis for his treatment of the archetype of transformation expressed in the three stages of the Hero’s journey: departure, initiation, and return (Campbell, 1949).

My own interest is not specifically with transformative ritual or mythology, but rather with what Gregory Bateson might call “the pattern that connects” these areas (Bateson, 2002). I’m looking at a pattern which acts across scales, and thus can apply to ritual transformation as well as to smaller, non-ritualized transformations that are a part of the natural flow of daily life, such as shifts in perspective through casual conversation, or transformations across whole life-stages. The approaches of Gennep and Turner are firmly anthropological, and approach transformation primarily as a cultural phenomenon (i.e. through a shared language of ritual); I am interested in patterns of transformation that span personal, social, and transpersonal (spiritual) realms, across boundaries of gender and culture.

In the psychological literature, Jung’s idea of individuation seems to be a major inspiration, showing up in a number of works as a way to contextualize the transformative process (Bachant, 1974; Boyd, 1994; Kay, 2005; Kenney, 2007; Linehan, 2003; Persaud, 2000). Jung, who recontextualized alchemy as a language of the unconscious, recognizes the existence of patterns beyond the individual psyche, arising from a collective unconscious of humanity. Alchemical works were seen as forays into the collective unconscious as an early sort of psychology, and the alchemist’s task was linked directly to the process of individuation. Moreover, Jung identified some of the recurrent contents of the collective unconscious, calling them archetypes, such as the Hero, the Trickster, Rebirth, the Wise Old Woman, and, more importantly, the Shadow, Self, anima, and animus.

The elemental cycle, as I understand it, has an archetypal nature that is similar to, but also somewhat distinct from the Jungian sense of the term. Elucidating this difference is tricky. Jung, in his later years, distinguishes between the archetypes and archetypal representations (Jung, 1959b, p. 83). The elemental cycle, inasmuch as it relies upon the particularity of images associated with the four elements, is an archetypal representation (this is why the alchemical language is not required to speak about the archetype at work in the elemental cycle—the active realm standing behind this particular representation has an essentially infinite number of possible expressions in consciousness). The archetype itself remains unseen, and cannot be directly represented within normal human consciousness 2, whereas archetypal representations are always mediated by consciousness (Jung, 1959b, pp. 83-84). Indeed, we can simply say that archetypal representations, as the term suggests, arise through the particular meeting of the individual consciousness and the trans-individual archetype itself.

Jung makes a distinction between different unconscious contents by pointing out the reciprocal polarity that exists between the instinctual and spiritual in the human being. If the conscious life is represented as the visible spectrum of light, then the instinctual realm—the infrared—arises out of the part of the unconscious that is connected to matter, which “gradually passes over into the physiology of the organism” (Jung, 1959b, p. 85). Similarly, the spiritual in the human being—the ultraviolet—arises out of the part of the unconscious that is connected to the spiritual realm. Both the material and spiritual realms are transcendent, and cannot be directly grasped in the psychic realm (the visual spectrum). The material realm, when it comes into contact with the psyche, produces an instinctual consciousness. We could also say that when consciousness traces itself back through what appears to it instinctually, it necessarily fades out and disappears into the material of the organism. A similar situation exists on the ultraviolet side of consciousness, where we encounter not matter, but the archetypes, which are equally transcendent of the psychic realm as matter itself. Archetypes are thus spiritual in nature (Jung, 1959b, p. 86).

In his works, Jung almost exclusively (and by his own admission (Jung, 1959b, p. 85)) deals with the archetypes in a way that is directly linked to human experiences. Indeed, the archetypes are even seen as having their home in the collective unconscious, which “designates all the structural and functional areas which are common to the human psyche per se” (De Laszlo, 1959, p. ix). Jung does not speak about archetypes in a way that attempts to move beyond or connect to realms outside the human psyche—archetypes are always applied to human beings.

The elemental cycle certainly applies to human consciousness, and indeed can be thought of as a way in which to structure human consciousness. At the same time, it appears that when structured in this way, the same pattern can be perceived in transformative processes which are manifestly not human in nature or origin, such as the growth of a plant, atmospheric phenomena, or quantum mechanical processes. In this sense, the elemental cycle, as an archetype, seems to operate in a transhuman way, despite the condition that its perception takes place in human consciousness. Jung would not apply the archetype of the Mother to, say, a river, whereas the elemental cycle has no trouble working in this kind of arena.

It is not entirely certain to me that this understanding of the nature of the archetype (in its transhumant character) would be alien to Jung. Indeed, he seemed to leave (at least implicitly) the possibility of this higher-order level of archetype open, as evinced by the following excerpt:

Since psyche and matter are contained in one and the same world, and moreover are in continuous contact with one another and ultimately rest on irrepresentable, transcendental factors, it is not only possible but fairly probable, even, that matter and psyche are two different aspects of one and the same thing.” (Jung, 1959b, p. 85)

If the material and psychic realms do not have a separated, dual existence, but stand much more as mutual mirror images to each other, then it would not be problematic to expect a class of archetypes that operate in the psychic and material simultaneously. Indeed, Jung himself seems to have almost explicated this potential when he speaks of “another class of archetypes which one would call the archetypes of transformation. They are not personalities, but are typical situations, places, ways and means, that symbolize the kind of transformation in question” (Jung, 1959a, p. 322, original italics). Unfortunately Jung does not elaborate on this point. Needless to say, my understanding of the elemental cycle, as an archetype of transformation, can be applied to natural and spiritual realms as well as to the human.

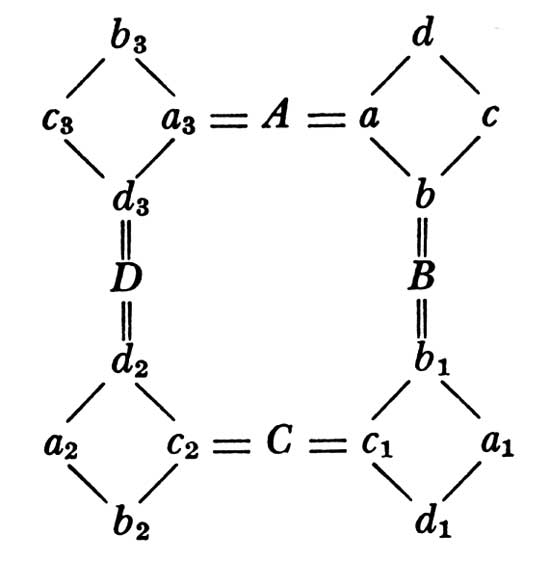

Jung, in his Aion (1978) even goes so far as to deal explicitly with a four-stage picture of transformation 3. Although he doesn’t speak on the matter of whether this quaternion series, organized into a wheel or rotunda, applies to material as well as psychic realms, he does—significantly, if unconsciously—immediately bring up once more the intimate connection between physics and the psyche mentioned above (Jung, 1978, p. 261). Jung indicates that the cyclical four-stage formula “reproduces exactly the essential features of the symbolic process of transformation” (Jung, 1978, p. 259).

Figure 1 - Jung's “formula” of the

four-fold process of transformation (Jung, 1978, p. 259)

Is it any wonder, then, that Jung identifies four stages of psychotherapy: confession, explanation, education, and transformation (Meadow, 1989), given that the goal of psychotherapy is transformation? Jung’s work, although very enticing, leaves out at least as much as it includes with respect to the four-fold archetype of transformation.

My master’s thesis has attempted to explore the breadth of the archetype, including how it applies in a number of non-human instances. My present inquiry deals more with its applicability to specifically human transformation, but across a wide variety of situations. In this sense, I am attempting to follow up on Jung’s statement that the four-fold cycle operates as an exact symbolic picture of the transformative process.

Tyler Volk, in his book Across Space, Time, and Mind (1995), speaks of metapatterns (Volk, 1995, p. vii), following Bateson’s single mention of this term: “My central thesis can now be approached in words: The pattern which connects is a metapattern. It is a pattern of patterns. It is that metapattern which defines the vast generalization that, indeed, it is patterns which connect.” (Bateson, 2002, p. 8) This language is very different than the psychological language of Jung, and has roots more in cybernetics and general systems theory. Volk, a professor of biology at New York University with a PhD in atmospheric science, approaches the idea of metapatterns with a very strong background in the physical and biological sciences, but (as the title of the book indicates) uses the term metapattern in a way that naturally spans physical and mental realms. Volk identifies ten such metapatterns: spheres, sheets/tubes, borders, binaries, centers, layers, calendars, arrows, breaks, and cycles (Volk, 1995).

Volk’s metapatterns only address transformation at a very superficial level, where he briefly mentions transformation in connection with breaks (in the context of stages) and cycles. A thorough treatment of transformations is not Volk’s goal, but the metapatterns that he addresses are quite closely linked with transformation (each is embedded in the other at various levels). Volk’s main contribution to an understanding of transformation is twofold: first, the concatenation of a large amount of brief factual examples that help show the need for the organizing concept of the metapattern, and (more importantly for the present discussion) a demonstration of the kind of thinking required to make use of the concept, which he defines as “attractors—functional universals for forms in space, processes in time, and concepts in mind” (Volk, 1995, p. ix) This definition of metapattern is very close to the extended sense of archetype as discussed above.

The elemental cycle, as an archetype of transformation, is necessarily found in time. It is an archetype not of things but of processes. It describes patterns in processes. Because things are a manifestation or result of these processes (although it is likely more accurate to say that there simply are no things, if thing means to be ontologically separated from the continual processes of its coming into being), sometimes the elemental cycle appears in a more static way. Nevertheless, the elemental cycle is itself a process, and cannot be accurately grasped through any non-moving imagination or representation. Pictures of the elemental cycle, when held inwardly as a thing, only serve to destroy all but the corpse of the activity at work in the archetype.

I point this out because my inquiry involves an attempt to examine transformations, and to see the extent to which the elemental cycle usefully contextualizes how transformation occurs. It would be easy for this to become just another model, a set of static categories into which everything gets shoved equally. It should be clear that this potential is well-understood, as is required if the approach is to be transdisciplinary. We could say that the elemental cycle invites a self-reflexive epistemology about its own content. This keeps the field of possible ways in which to approach it open, rather than requiring that it be understood in only one way.

Montuori points out that “in our society, information must be generated” (Montuori, 1998, p. 5), as if on command. Wilshire (1990) shows how the whole Western university system, in the 19th century, began to lead itself towards greater and greater “professionalism”, where it got itself “into the business of producing its own producers of ‘useable knowledge’” (Wilshire, 1990, p. 62). Montuori and Wilshire warn of the dangers of this system of knowledge production. For Wilshire, the consequence is the death of education, which is rightly a moral enterprise (Wilshire, 1990, p. xxiii), while Montuori cites the destruction of creativity and a turning away from inquiry as love of knowledge for its own sake (Montuori, 1998, pp. 13, 18-19). Montuori thus calls for a fundamentally new mode of discourse, which attempts to steer clear of the patterns that have historically served to reduce education to the production of knowledge and knowledge to its usage (Montuori, 1998, p. 20). The new mode of discourse, which he calls creative inquiry, draws upon and supports the picture of transdisciplinarity painted by Morin and Nicolescu.

The elemental cycle, by its very nature, seems to align itself with this kind of view, and my own passion for the inquiry stems in its greater part simply from a fascination with how my concept of the elemental cycle, over time, has changed me. I have been changed through work with the elemental cycle, and the elemental cycle has reciprocally and recursively been changed through my work. I have the benefit of being quite aware of my relationship to it from the very beginning, almost exactly ten years ago, and have consciously traced my successively deeper and more thorough understanding of its subtleties and complexities over that time. Therefore I am very sensitive to the different ways in which the elemental cycle can present itself, and recognize that—like any process—it takes time to ripen. Part of my interest is in pointing out and helping to engender this very ripening for its own sake, as a way of keeping us organically embedded in a process of ongoing discovery, whatever the topic. One reason the elemental cycle is so exciting to me is because its own actual content points towards this same insight: understanding the elemental cycle, in a very real sense, requires its own enactment. Indeed, as Montuori, citing Tarthang Tulku, states, “the attitudes we adopt in carrying out our investigation shape the attributes we find in the world we investigate” (Montuori, 1998, p. 27). This is an insight that the alchemists knew well, which Dennis Klocek phrases in a direct and succinct manner: “how you get there is what you get” (Klocek, personal communication).

The dominant ways of talking about transformation are generally not so subtle. Often, transformation is described as occurring in a linear fashion, from A to B. Sometimes transformation is presented in cyclical fashion (as when connected to seasons), but then often this cycle becomes simply a repeated pattern which is itself static. Sometimes stages of transformation are elucidated, but almost invariably these stages are taken from or applied to a very particular context. Thus, the process of transformation for an addict attempting to get clean may not seem (on the surface at least) very connected to the process of transformation connected to a change of heart as a result of seeing, for example, a beggar on the street. Moreover most studies on transformation tend to focus on transformations that are highly significant or connected to circumstances which, when placed alongside life as a whole, stand out in some significant way.

All of this is to say that most work concerning transformation has occurred within disciplinary boundaries (psychology, education, economics, etc.), and doesn’t thereby benefit from what Montuori calls “the promise of transdisciplinarity” (Montuori, 2005). Montuori (2005) cites five cornerstones of the transdisciplinary project. Transdisciplinarity is:

- inquiry-driven rather than exclusively discipline-driven

- meta-paradigmatic rather than exclusively intra-paradigmatic

- informed by a kind of thinking that is creative, contextualizing, and connective (Morin’s “complex thought”)

- inquiry as a creative process that combines rigor and imagination (Montuori, 2005, p. 154)

Certainly working with the elemental cycle does not fit into any disciplinary lines. What discipline would it be? It’s not strictly psychology, nor is it strictly alchemy (as if that were an accepted discipline anyway). It isn’t even strictly anthroposophical, despite this being the most likely arena for its ready reception. The inquiry is meta-paradigmatic in that the topic, and my approach to the topic, do not prescribe to a singular, absolute point of view or way of knowing, but rather includes, even requires, multiple ways of knowing. At the same time, the inquiry attempts to span some of the boundaries of the dominant paradigm by explicitly and repeatedly crossing between the material and non-material worlds, but in such a way as to lessen, through the development of a new way of seeing, the potentially assumed differences between these realms. As such, my approach calls for constant connection and re-connection, as well as contextualization and re-contextualization. My goal is, in part, to contextualize the elemental cycle in such a way that others can re-contextualize it in new ways, to connect it to specific phenomena so that others can connect it to completely different phenomena. The process therefore has to walk the creative edge between rigor and imagination, between sclerosis and inflammation, between center and periphery.

In order to help achieve this goal, I think it will be important to approach the elemental cycle with the language and concepts provided by cybernetics (particularly second-order cybernetics) and complexity. The alchemical background of the elemental cycle provides a very rich language for the soul (as Jung pointed out to the psychologists), but generally speaking keeps those who fall into the currently dominant paradigm of objectivity provided by material science at bay. This is an unfortunate tragedy, and I think that a marriage between alchemy and cybernetics will produce great fruit for psychologists as well as natural scientists—not to mention many others, such as teachers, contemplatives, doctors, etc.

Take for example the following principle of cybernetics, explicated by Bradford Keeney, a student of both von Foerster and Bateson: “Cybernetics proposes that change cannot be found without a roof of stability over its head. Similarly, stability will always be rooted to underlying processes of change” (Keeney, 1983, p. 70). This is precisely the kind of insight produced by working with the elemental cycle, which in alchemical language would be expressed by relating the qualities of the elements to each other: Earth always has a Fire inside it, and every Fire process leads to a New Earth. For most people, it is much easier to understand the former, precisely because we generally do not develop the capacity to think in metaphorical images. The dreaming process shows us that image production is a foundational capacity of the mind; the modern alchemist simply develops this process into a conscious art in connection with the nature of the world and the nature of the soul. Nevertheless, cybernetics can offer alchemy a more accessibly rigorous formulation, while alchemy can offer cybernetics a more direct connection with soul-processes (an impulse that would have greatly benefitted cybernetics researchers who attempted to use its principles in a purely mechanistic way, i.e. to create artificial intelligence).

Ultimately, what I am aiming at is a transformation of human consciousness, very much in line with the goal of transdisciplinarity, so that when faced with transformation—that is, when faced with itself, and with life itself—it finds the capacity to be robust, flexible, adaptive, connected, connecting, contextual, and able to hold and work with and through paradox without collapsing into dichotomous formulations or fundamentalism of any sort. Further work with higher-order cybernetics, general systems theory, and complexity science will help re-contextualize my understanding of the elemental cycle in a way that will make it much more robust and presentable, in a way that actually helps to foster a transformation of consciousness. In particular cybernetics seems to be useful for this task because it can deal with both material and non-material realms equally. Keeney cites one of the founders of cybernetics, Ross Ashby, in this connection:

Cybernetics started by being closely associated in many ways with physics, but it depends in no essential way on the laws of physics or on the properties of matter. Cybernetics deals with all forms of behavior….The materiality is irrelevant, and so is the holding or not of the ordinary laws of physics. The truths of cybernetics are not conditional on their being derived from some other branch of science. Cybernetics has its own foundations.” (Keeney, 1983, p. 62, original italics)

Suffice it to say that this kind of approach, informed by the concepts and language of cybernetics, is not easy to find in the discourse around transformation. Keeney’s (1983) work Aesthetics of Change is one place where a cybernetic epistemology is thoroughly applied to transformation—in this case in the context of family therapy. Luckily I am not the first person to explicitly notice a connection between complex thought, alchemy, and depth psychology: John S. Uubersax (2006) has written a short document entitled “On the Relevance of Alchemical Literature for a Systems Theory Approach to Depth Psychology”, which—significantly—includes the statement that “a literature search has failed to identify existing articles on this subject” (Uebersax, 2006). I hope that more such resources will be forthcoming, but part of my purpose is to help fill this gap.

Clearly cybernetics and alchemy need to get together at a bar and strike up a conversation. They’ve met before, actually, in a kind of timid way; the alchemical symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake which eats its own tail, repeatedly appears in cybernetic works as a way of representing the key principle of recursion. (“Hello Recursion, nice to see you again, here at the end of the beginning!”) Nevertheless, a more formal introduction seems like a good idea, and if they don’t have the nerves to do it themselves, it seems like I’ll have to make the attempt as a third party matchmaker.

References

Bachant, J. L. (1974). Processes of transformation in the structure of the ego during emotion within the theoretical framework of C. G. Jung. New School for Social Research, New York.

Bateson, G. (2002). Mind and nature : a necessary unity. Cresskill, N.J.: Hampton Press.

Bockemühl, J. (1985). Toward a phenomenology of the etheric world: investigations into the life of nature and man. Spring Valley, N.Y.: Anthroposophic Press.

Boyd, R. D. (1994). Personal transformations in small groups: A Jungian perspective. New York: Routledge.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. [New York]: Pantheon Books.

De Laszlo, V. S. (1959). Introduction. In V. S. De Laszlo (Ed.), The basic writings of C.G. Jung. New York: Modern Library.

Gennep, A. v. (1960). The rites of passage. London: Routledge & Paul.

Gordon, L. R. (2006). Disciplinary decadence : living thought in trying times. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Hoffmann, N. (2007). Goethe's science of living form : the artistic stages. Hillsdale, NY: Adonis Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959a). Archetypes of the collective unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In V. S. De Laszlo (Ed.), The basic writings of C.G. Jung. New York: Modern Library.

Jung, C. G. (1959b). On the nature of the psyche (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In V. S. De Laszlo (Ed.), The basic writings of C.G. Jung. New York: Modern Library.

Jung, C. G. (1978). Aion: researches into the phenomenology of the self (2d ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Kay, P. (2005). Toward a psychological theory of spiritual transformation. Chicago Theological Seminary.

Keeney, B. P. (1983). Aesthetics of change. New York: Guilford Press.

Kenney, M. A. (2007). Mysterious chrysalis: A phenomenological study of personal transformation. Pacifica Graduate Institute.

Klocek, D. (1998). Seeking spirit vision. Fair Oaks, CA: Rudolf Steiner College Press.

Klocek, D. (2005). The seer's handbook : a guide to higher perception. Great Barrington, MA: Steinerbooks.

Linehan, W. (2003). Combat and transformation: The necessity of madness, the numinous, and reflection. Pacifica Graduate Institute.

Meadow, M. J. (1989). Four stages of Spiritual Experience: A comparison of the Ignatian Exercises and Jungian Psychotherapy. Pastoral Psychology, 37(3), 172-191.

Montuori, A. (1998). Creative inquiry : from instrumental knowing to love of knowledge. In J. Petrankar (Ed.), Light of knowledge. Oakland: Dharma Publishing.

Montuori, A. (2005). Gregory Bateson and the promise of transdisciplinarity. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 12(1-2).

Montuori, A. (In Press). Transdisciplinarity and creative inquiry in transformative education : researching the research degree. In M. Maldonato & R. Pietrobon (Eds.), Research on research : a transdisciplinary study of research. Brighton & Portland: Sussex Academic.

Morin, E. (2008). On complexity. Cresskill, N.J.: Hampton Press.

Nicolescu, B. (2008). In vitro and in vivo knowledge -- methodology of transdisciplinarity. In B. Nicolescu (Ed.), Transdisciplinarity : theory and practice. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Persaud, S. M. (2000). Grace unfolding: Self-transformation as a sacred, transgressive art of listening to the inner voice. A Jungian perspective. University of Victoria (Canada).

Turner, V. W. (1969). The ritual process: structure and anti-structure. London,: Routledge & K. Paul.

Uebersax, J. S. (2006). On the Relevance of Alchemical Literature for a Systems Theory Approach to Depth Psychology. Retrieved 3/15, 2009

Volk, T. (1995). Metapatterns across space, time, and mind. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wilshire, B. W. (1990). The moral collapse of the university : professionalism, purity, and alienation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Endnotes:

2 (Back) Whether this remains true for all possible states of consciousness is an open question.

3 (Back) It is interesting to note that Jung culminated this seminal work, his researches into the phenomenology of the Self, with an exploration of the quaternary process of transformation. Taken as a picture of the whole development of his thought, this fact (whether intended by Jung or not) seems significant given the present line of inquiry.