Sleep and Dreams in Anthroposophy

Seth Miller

12/06/06

Introduction

There are a number of approaches to dreams and dream interpretation, spanning the whole history of the human race and taking a number of different forms. In fact, there does not appear to be a single culture on the earth that does not in some way make room for the experience of dreaming in some way. In almost all cultures, dreaming is understood to be an important part of human experience. For example, dreams are thought to provide meaningful wisdom about oneself, one’s culture, or world events, or they can open a sacred space that connects us to higher realms. Dreams have been viewed as representing the subjectivity of the dreamer’s life, or objectively displaying future events. In the scientifically oriented modern cultures of the West, much of this type of significance is generally thought to be based on incorrect assumptions, and the focus has been on understanding what modern science assumes to be the basis of dreaming: the material brain. This has lead a number of researchers to believe that dreams are essentially entirely random brain events arising as an inevitable but meaningless consequence of the way our brains are wired – light shows in which our brains manufacture meaning and story out of something that is at its root entirely meaningless.

On the other hand, out of the “Western mind” have also come a number of people whose work with dreams attempts to bring some of the tools and rigor of science to bear on this very difficult arena. without the assumption that they are meaningless. The first steps in this way were made by Freud, Jung, and their followers, and has been in continual development ever since. At the very time in which Freud and Jung were laying the groundwork for generations of dream-researchers to come, Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian scientist and gifted clairvoyant, was developing a comprehensive picture of the human being called anthroposophy, or spiritual science, that dealt with the nature of sleep and dreams in an entirely different way – out of a cosmologically rich background that coherently includes both the physical and spiritual worlds. What does anthroposophy have to say about the nature of sleep and dreams, and what does such an understanding mean for modern humans? Addressing these questions will hopefully provide the reader with a perspective that is not well-represented in modern dream research, and will perhaps reframe some prevalent ideas about the nature and purpose of dreaming in a useful and insightful way.

Anthroposophy and Dreams

Anthroposophy is a comprehensive worldview primarily developed by Rudolf Steiner at the beginning of the 20th century that contextualizes the human being according to a science of the spirit. It attempts to reawaken human beings to the realities of the spiritual worlds while simultaneously providing practical tools for self-development, social transformation, educational, farming, and medical techniques, as well as developing new artistic modes of expression. In one way, it can be viewed as a method of approaching the transformation of consciousness on scales both cosmic and human; in another it can be seen as a modern path of awakening to the actualities and potentialities of the human spirit. It is too deep and broad to easily define, but suffice it to say that anthroposophy takes as a central theme the development of human consciousness through all its stages and forms. As a part of this, the human experience of sleeping and dreaming is necessarily included.

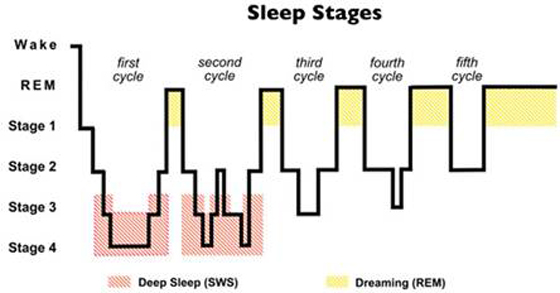

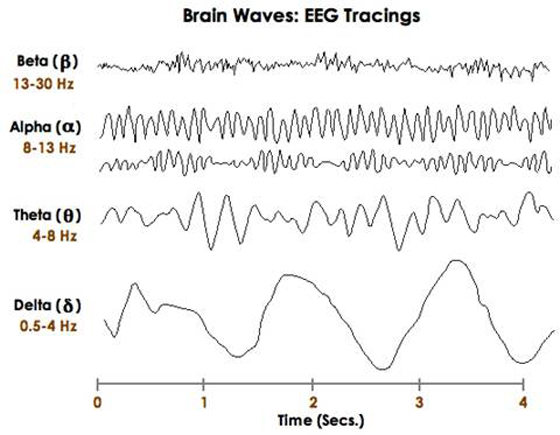

In order to understand the nature of dreams, we must examine the human consciousness in its awake state and its sleeping state. If we examine an EEG of an awake person who falls asleep, moves through periods of dreaming, and then awakens, we can see how the frequency and type of electrical activity varies according to a particular pattern (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1:

Figure 1 represents an average night of sleep, where the individual moves from waking into stages 1, 2, 3 and 4, then back up into a REM (rapid eye movement) period where dreaming occurs. This activity cycles about five times, with each REM period getting longer as the night progresses. The second figure shows what type of brainwave activity occurs in the various stages of sleep. The waking state is characterized by high-frequency beta activity, which gives way to slower frequency, higher amplitude waves as sleep deepens, moving quickly through calm wakefulness in alpha to light sleep in theta, and deep sleep in delta.

Figure 2:

It turns out that the brain’s activity in dreaming is very similar to its activity in the waking state – high frequency but low amplitude. We can therefore say that dreaming is a state of consciousness between that of waking and dreamless (or non-REM) sleep. It is, in a way, a mixture of the state of wakefulness with that of sleep proper. In the dream state, we are not awake in the sense of having the capacities normally attributed to our normal, day-awake consciousness, such as the ability to think through a single logical, complex train of thought.

A modern scientific understanding of the reasons for this qualitative difference between waking and dreaming is generally attributed to very specific neurophysiological mechanisms. From the perspective of anthroposophy, this kind of treatment can only reach the level of a description of the physical body when the human is in the dream state, but does not constitute an explanation, because it is unable to trace the non-physical aspects of the human being through sleep and dreaming. This is not at all to say that what modern science discovers about the brain is false – simply that it is only one part of a whole picture, and that it would be an error to assume the single part to constitute the entirety.

Here, anthroposophy offers insight into the nature of dreaming and sleeping the understanding of which requires a wider conception of the human being. Rather than consisting solely of a physical body, anthroposophy, like many other spiritual traditions the world over, recognizes other members of the human being which exist at various non-physical levels. The physical body can be considered to be the “lowest” or most dense aspect of the human being, which we share with the mineral world. But closely connected to our physical body is what could be called a life body, or etheric body, which is responsible for the organization and transformation of the physical substances of the body in the processes of growth and decay. Without an etheric body we would be corpses immediately subject to the purely physical law of entropy, but with it we can defy this inevitable physical breakdown for a time and share along with the plant realm the ability to grow, reproduce, and decay according to lawful patterns.

“Above” the etheric body anthroposophy identifies the part of the human being that is shared with the animal kingdom, the astral body, through which we experience desire, passion, antipathy, pain, pleasure and all other feelings. The astral body, which can be called the soul, is responsible for connecting human experience to the worlds that surround us through our variegated sense life. Yet humanity has an additional member, which can be called the ego, or I-being, which sets us apart from the animal kingdom. It is the part of us that can say “I” to itself, without reference to any outer sense experience. The I-being is the lowest member of the human’s spiritual nature. The human being then is comprised of body (physical and etheric), soul (astral), and spirit (I-being), working as a united, interweaving whole.

From the perspective of anthroposophy, when a person goes to sleep, the physical and etheric bodies lie together on the bed, while the astral body and ego separate and leave the two lower members. The physical body is kept from the process of dissolution in sleep because the etheric body remains, engendering all the necessary functions to sustain life – but not consciousness. Consciousness is a function of the ego, and the nature of the experiences available to it depend upon its level of development with respect to the other members of the human organism (the physical, etheric and astral).1 Because of the present configuration of the ego and its relation to the lower members, the ego cannot generally remain awake without contact with the etheric and physical bodies.

In dreamless sleep, because the astral and ego are separated from the lower bodies, the consciousness of the ego becomes dim to the point of complete unconsciousness. It should not be imagined that the astral and ego separate completely from the lower bodies, but that still a slight connection remains between them.2 This connection is what allows a person to be woken by physical events, such as an alarm clock; if the ego and astral separated completely, the etheric body would soon lose its ability to maintain the physical form, and death would result.

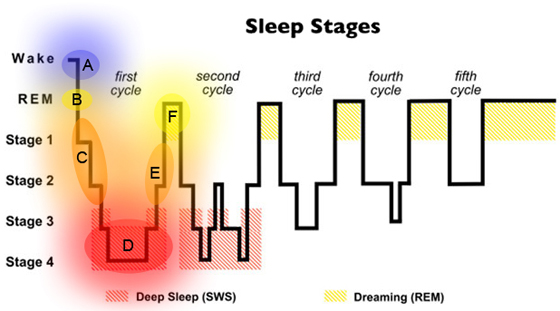

In terms of dreaming sleep, the ego and astral body turn back towards the physical and etheric bodies, but not to the point of fully uniting with them. Rather it is as if they hover nearby, between the physical world and the world that could be called the astral world, in which the ego and astral body move when in dreamless sleep. Thus, we can see a correspondence between the modern scientific conception of the stages of sleep with the description of sleep provided through anthroposophical insight. A modification of figure 1 (see figure 3 below) can help bring this to light.

Figure 3:

In the awake state at A, the ego, astral, etheric, and physical bodies are united, and day-awake consciousness results. Then, as relaxation towards sleep occurs, the ego and astral body begin to loosen slightly from the etheric and physical bodies, corresponding with the shift to alpha waves. Skipping point B for the moment, we can note that at C, the ego and astral bodies are in further separation, until at D they are almost completely separated. Then, over the course of the night, the ego and astral bodies will begin to turn back (E) towards the physical and etheric bodies lying on the bed. At F, the astral and ego are close enough to the etheric and physical bodies that enough support exists for the ego to have the experience of dreaming, but not enough that full, day-awake consciousness is possible. Before further elaboration of this diagram is possible, it will be useful to examine this process from a slightly different angle.

The Human Organism in Sleep and Dreams

The astral body, or soul (distinct from the spirit), is the part of the human organism that is capable of forming symbols. One of its functions is to take in the world through sensorial perception, which it reflects it towards the ego. It is not able, at first, to do this in a purely objective manner, nor is the ego necessarily capable of understanding what the astral body brings it. Presently the ego is formed in such a way that it is most able to take hold of and penetrate the pictures that are given to it by the astral body through its contact with the physical body, and when it does so, it experiences thinking. In particular, therefore, we are most awake to the outer, physical world because of the level of development of our physical senses. Our ego thus feels itself to be awake when it is in contact with the physical world through the senses. The thoughts of our day-awake consciousness are tied closely to the physical world for just this reason, and fill the bulk of our waking experience.

But in dreamless sleep, it is precisely our physical senses that become dim for us, to the point of complete non-existence. Our astral body and ego recede from the physical and etheric bodies, and without training, the ego cannot remain awake to the pictures that then flow into the astral body – not from the physical world which it has just turned away from, but from the wider astral and spiritual worlds in which it is now embedded. We experience a loss of not just the capacity for rational thought, but also of the ego’s own ability to perceive itself.

In between the astral and physical bodies lies the etheric body, working to metabolize, repair, and regulate all the activity of the life organs. The etheric body can be thought of as a tapestry of weaving forces that connect strongly to the physical body, penetrating it through and through with activity. In order to understand dreaming, it is towards the etheric body that we must look.

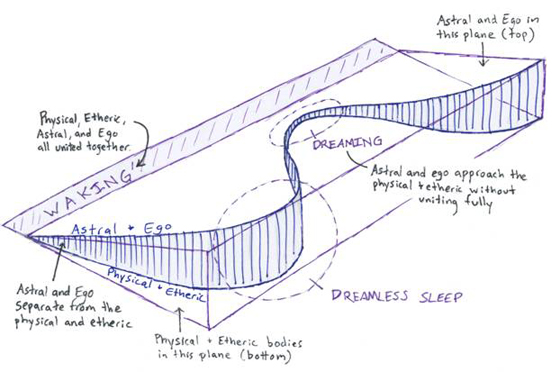

From the perspective of anthroposophy, dreaming is precisely the state of consciousness experienced by the ego when it unites itself with the etheric body. Becoming aware of passing through the etheric body gives the ego the experience of the dream, and this experience comes through and is mediated by the symbol-forming capacity of the astral body. The dream content itself has its source in the etheric body, but the astral body transforms that primal content into symbols that are presented to the ego. It is as if the weaving etheric forces have to become clothed in the symbols formed by the astral body before the ego can awaken to them. It is just this process that gives the dream its dreamlike quality; we have the sense when awake that there is more to our dream than the manifest form in which it is presented to us, but that somehow beneath this exterior a deeper reality lies in wait. This deeper reality is, at first, the etheric body. Figure 4 represents a further modification of figure 1 to include the separation of the astral and ego from the physical and etheric during the various stages of sleep.

Figure 4:

Further Considerations

The above discussion builds up the basic picture of the various stages of normal human consciousness as it moves continually through the daily cycle of sleeping and waking. When awake, the ego and astral body are united with the etheric and physical bodies, and when asleep, the ego and astral leave the etheric and physical. During the night, the ego and astral bodies return to the etheric and physical without joining them, but they are united enough that the ego experiences some of the activity occurring in the etheric body. Now the question may arise, of what use are such ideas about sleep and dreaming? In fact, the anthroposophical understanding of sleep and dreams can be quite illuminating. For example, what does the above picture say about a fact pointed out by William Dement (Dement 1999, p.295), the foremost pioneer of sleep research, to the effect that sometimes dreaming can take place in non-REM sleep, but only about 10 percent of the time?

If we understand dreams as arising from the ego lingering in the etheric body before fully uniting with it and with the physical body, this curious fact makes sense. In order to experience the waking state, the human ego and astral must penetrate fully into the physical and etheric bodies. Normally the process of transitioning from dreamless sleep to being awake can happen very quickly, almost instantaneously. In such a case, the ego does not linger in the etheric body, and no content from the etheric body is formed into symbols by the astral body; we simply wake up and report that we were not dreaming. If a subject is being awakened by a sleep researcher during a non-REM period, then the astral and ego bodies are quite disconnected with the etheric and physical bodies, and the return to the body is quick enough to hinder any dream formation. At the same time, the ego and astral body must pass through and into the etheric body on the way to waking, and what will determine whether or not a dream occurs has to do with the precise way in which the waking occurs.

I suggest that the 10 percent of non-REM dreams reported by sleep researchers can be correlated with the particular way in which the subject transitions from sleeping to waking in each individual case. The anthroposophical view would predict that if waking occurred very quickly from non-REM sleep, the subject would be less likely to report dream experiences. The converse of this would also be predicted: the incidence of dream reports should increase when waking from non-REM sleep with a lengthier sleeping to waking transition period.

Further fascinating correspondences with modern sleep and dream research can be seen. For example, during REM sleep, it is noted that PET scans show decreased activity in the primary visual cortex, along with decreased activity in other areas of the brain that process sensory information. Additionally, “the frontal lobes – whose functions include short-term memory, planning and executing thoughts and actions, and integrating data from other parts of the brain – are also passive. What remains highly active are the brain’s emotional and long-term memory centers.” (Dement, 1999, p.305)

From the anthroposophical perspective, of which only the tiniest slice can be presented here, our capacities for both thinking and memory are possible only because we have an etheric body – while our capacity for feeling, associated with the astral body, is closely allied with the state of dreaming. Let us take these two elements separately.

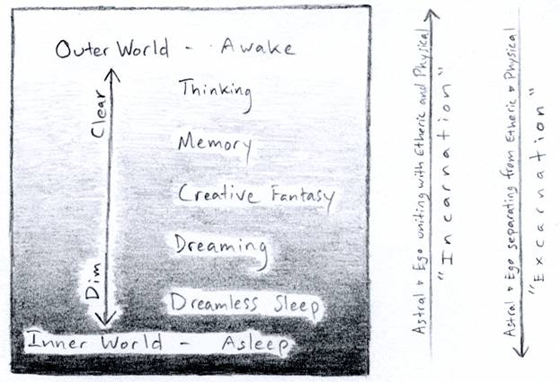

When we examine the way in which the astral and ego come back into contact with the physical and etheric bodies at the end of sleep, we can notice how this process has definite ramifications for consciousness. Consider the following diagram.

Figure 5:

This diagram is an attempt to illustrate how more than just dreaming and sleeping are associated with the relations between the different members of the human organism. In particular, it depicts the level of consciousness able to be present for an ego when it is more or less united with the lower bodies. The whole process a human being goes through over the course of a full day and night cycle can be understood as occurring between the polarities of incarnation and excarnation.

In the state of greatest excarnation, the normal human ego is not able to be awake to its surroundings – thus the worlds through which it travels are dim to the point of total obscurity. At this point, the autonomy of the astral body is at its greatest, but as the ego follows the astral body through its spiritual surroundings, it cannot receive what could be present for it if the ego were strengthened. This is the state of dreamless sleep, of which we can have only the vaguest impression upon waking, as if we have just come from somewhere but cannot recall anything more.

The ego, with the astral body, then descends so that they are penetrating the etheric body to a greater or lesser extent. Here, the astral body takes in and re-presents the weaving forces of the etheric body to the ego in symbolic form – the dream state proper. The soul life – held within the astral body – experiences a loss of autonomy, as if it was water vapor forced now to precipitate into many droplets. Yet still, in dreaming, the astral body is only lightly bound to the lower members, and thus is free to create according to its symbolic capacity – but the basic source of its creation is at first the etheric body itself. Thus many different types of manifest dream symbol can arise from a single underlying etheric pattern. At this stage the astral body is alive with feelings of all kinds that are enkindled in it by its contact with the etheric body, and it may form any number of symbols out of this contact – but what is essential to the astral body is the mood of the dream, which can be expressed in any number of ways.3

In the dream, the soul perceives primarily itself – not the outer world – but it does so in a dim fashion, as if masked. Because the ego and astral are not yet in strong contact with the physical body, the thinking functions are weakened, and the dream is therefore taken as reality by the ego. Yet the content of the dream is not arbitrary; Steiner gives an interesting picture of it in this way:

People have become aware that the world of images the dream conjures up has some connection with the vague sensation of self. This appears, as it were, as an empty canvas on which the dream paints its own pictures. And then it is realized that the canvas is really itself the painter painting on and within itself. (Steiner, 1923).

The self-content arises primarily out of the etheric body. Because the physical body is almost entirely dimmed from consciousness in the dream, the parts of the brain that deal with sensory information are more quiescent than during waking life. Yet what remains active are the long-term memory and emotional centers – the limbic structures of the brain. The memory provides the self-content of the dream through the etheric body, but just as the ego mistakes the dream-nature for reality, it is unaware that the content of the dream is provided from its lower member. The astral body then turns this into symbols and adds to it the emotional drama of the dream, the physical traces of which are supported by the limbic area of the brain in particular.

Proceeding forward with the incarnating process of the human being we can note how the astral body is more and more bound to the physical body, so that it becomes more restricted in its symbol formation. The process of incarnation proceeds and we begin to awaken – but at first our wakefulness is not like the wakefulness we will have later in the morning. Just after passing through the morning gate of sleep we are in a sort of semi-conscious state where images of various kinds flit in and out of awareness. Quickly, the images begin to have the tendency to take on the character of creative fantasy, where real and imaginary elements mingle freely.4 Here the astral body is compelled to emulate what exists in the world of the senses, but still with some freedom. This is a result of the astral and ego coming into stronger connection with the etheric and physical bodies.

If we take this process further, we can see how what exists for us in our conscious experience of memory requires a further level of penetration of the astral body and ego into the etheric and physical bodies. Conscious memory only exists when the astral body penetrates even more strongly into the physical body than it does in the dream – but even here a small bit of autonomy still exists for it, and our memories are not entirely infallible. Our memories are particularly undependable when the memory in question is associated with strong feelings, precisely because the activity of the astral body can easily overwhelm the more delicate process of thinking required to test the objectivity of the memory, which requires a fully awake ego.

Finally, in the most awake state, the astral and ego are fully united with the physical and etheric bodies, and the dreaming force of the soul is entirely surrendered to the working of the physical body. When the astral body surrenders itself to the physical body in this way, it also becomes harnessed to external physical laws. Its autonomy is further restricted, and “the means whereby the soul adapts to the existence of nature is experienced as logic.” (Steiner, 1923). Our capacity for rational, day-awake thinking arises out of the binding of the astral body to the laws of the physical body – the laws of the external world. Thus the last parts of the body to awaken and become permeated with the activity of the astral body are the frontal lobes of the brain, the seat of rational thinking and logic.

Based on the above picture we can see how the physical brain states of the sleeping human correlate with what is brought to light by anthroposophical considerations. The physical brain – or more specifically, the whole branching nervous system, including the gut – is the material seat of the spiritual process of thinking. In order to have the capacity to think, the ego and astral bodies must work directly with the etheric and physical bodies. If they work only with the etheric forces and do not penetrate as far as the physical body itself, then the various states described above result: dreaming (of various kinds), creative fantasy, and memory. The synchronized, slow wave EEG of a brain in non-REM sleep corresponds with the way in which the etheric body takes hold of the physical body to build it up while the astral and ego bodies are absent. The selective activation of the limbic system in the REM state corresponds with the increased activity of the astral body in the etheric body (which in turn works into the actual physical body). This activity is strong enough to activate the long-term memory centers and the emotional centers, but is not yet strong enough to fully activate the sensorial components of the brain. Only when the astral body and ego unite fully with the etheric and physical bodies, having passed through the morning gate of sleep, do the parts of the brain necessary for sense perception and thinking become activated. It is in such a way that anthroposophy can help illuminate, extend, and contextualize the facts discovered through normal physical science. Only the briefest considerations are taken up here, but the interested reader is referred to the works listed below.

References:

Dement, W. C. & Vaughan, C. (1999). The Promise of Sleep. New York: Dell Publishing.

Steiner, R. (1906). An Esoteric Cosmology: Eighteen lectures delivered in Paris, France from May 25 to June 14, 1906. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/EsoCosmo/19060528p01.html

Steiner, R. (1914). The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/Places/Dornach/19201217p01.html

Steiner, R. (1918). Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Books/GA010/English/GA010_c07.html

Steiner, R. (1921). Cosmic Forces in Man. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA/GA0209/19211127p01.html

Steiner, R. (1923). On the Life of the Soul. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Articles/OnSoul/OnSoul_e01.html

Steiner, R. (1925). Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts. Retrieved on 11/18/06 from http://wn.rsarchive.org/Books/GA026/English/RSP1973/GA026_c20.html

Endnotes:

1 (back) Additionally, as the I-being progresses in its evolution, it transforms the astral, etheric, and physical bodies into higher spiritual members that lie “above” the I-being, through which the ego lives consciously in higher spiritual worlds as an active member.

2 (back) Clairvoyants of various traditions have spoken of a luminous thread connecting the dreamer back to the physical body as seen by spiritual vision.

3 (back) Also it should be pointed out that a number of different types of dreams can result from the interplay of at least two basic factors: the strength of the ego to maintain an awake state and the level of contact between the ego and astral with the etheric and physical. For example, on the one hand we can imagine how the “night terror” arises spontaneously when a weak ego, through its astral body, experiences fundamental processes occurring in the etheric body. Such dreams have only the most basic content and a very vague level of symbolism. They occur more often in childhood, when the ego is just a glimmer on the horizon and the forces of the etheric body are bound strongly to the physical body, building bones, brains, muscles, and so forth.

On the other hand we can see how a strengthened ego, which can remain more awake to what occurs in the astral body during sleep as it leaves the etheric and physical bodies behind, can experience wholly different types of content, which become the basis for myths that are much less personal than the previous type of dream. Such dreams are often called “big dreams”, and have symbolic content which transcends the individual. Jung spent much of his time dealing with this kind of dream, which he referred to as the stemming from an archetypal realm. Anthroposophy provides insight into not only how such dreams arise, but also why they have the character that they do.

4 (back) This sequence may be more phenomenologically accessible (in opposite order) when going from waking to sleeping, as the transition period is often slightly longer than upon waking – particularly if one awakens with an alarm clock!