The Art of Nature:

Alchemy, Goethe, and a New Aesthetic Consciousness

By Seth Miller

12/19/09

Who possesses science and art

Possesses also religion:

Who possesses the first two not,

O grant him religion.

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Abstract

This essay explores the building of a new aesthetic consciousness, working out of insights from alchemy, into a new aesthetic method of observing brought forth by Goethe, and ending with a brief mention of the way this stream was taken further with the works of Rudolf Steiner. I present an evocative picture of the development of this new consciousness, which Goethe felt dissolved the subject/object boundary, and give a series of images and related videos as a part of a brief practical example of how this consciousness can be developed. I invite you, the reader, to participate actively in your reading of this work, as if you were viewing an artistic piece, to get into a mood suitable for engagement with the content herein.

Introduction

In some sense, all art begins with nature, the primal context within which consciousness—including aesthetic consciousness—evolves and transforms. Experiences of the aesthetic afforded through multimodal sensory contact with the natural world work on the individual in ways that no contrived art form can. The play of light and shadow, the perspectival shifting of shape and form, the ebb and flow of interweaving sounds, the wafting smells, the warmth or coolness of the air and ground… all these aspects and countless more coalesce into the complex experience of nature, which can radically modify our inner lives, and not just temporarily.

I distinctly remember when I was about 8 years old, wandering alone through the fields behind my house in Austin, Texas. After having traveled what seemed like a slightly dangerous distance (just enough to almost feel lost, and thus to be on the edge of adventure), I came unexpectedly through some trees into an idyllic meadow, covered with grass and wildflowers, and complete with flitting butterflies, a tiny gurgling stream, and a delicate breeze which wafted unidentifiably sweet smells to me. For some reason that summer day the elements were aligned in just the right way, and I was literally awestruck by what seemed a perfect scene. The impact of the essential beauty of this experience has stayed with me for my entire life. It was the first moment that I consciously remember becoming awake to nature as a being; it seemed that I was almost trespassing on some sacred ground—a ground that was perfect and whole in itself. The experience was (at least for an 8 year old) a sublime awakening to the sublime, and in some way marked the beginning of my capacity to experience aesthetically.

There seems to be a special relationship between consciousness and the “art” of nature. As beings that have evolved in the context of the natural world, we are ideally suited to experiencing its many facets, its tonality and gesture, and to take these sensations aesthetically rather than just practically. Indeed, some of the oldest art known seems clearly inspired by the human being’s connection to nature and its processes. This Paleolithic art, rather than being solely representational in nature, is evocative, and mixes the human and the natural together in a dancing flow, precisely because these two realms were not strictly separate, but were experienced intimately together.

Yet human consciousness is ever-evolving, as is our relationship with nature and its “art”. The modern sciences of ecology and complexity have gone a long way in providing clear evidential data that nature is not something separate from us, and that almost every aspect of human life, including inner life, arises within and partly from the complex interwoven connections to the outer sensory world. In quantum mechanics, it is understood that at a very fundamental level it is impossible to run an experiment that is fully isolated and free from extraneous inputs; isolation as a criterion is no longer tenable for a healthy scientific endeavor, which now must appropriately include wider “environmental” contexts to gain valid results. On another front advances in cognitive science have shown that the very roots of perception and consciousness are intimately entwined with the “outer” environment through complex, multi-layered feedback loops that span more than just the brain (1). Cybernetics, specifically second-order cybernetics, or the “cybernetics of cybernetics”, which is the science of recursion, has further explored the necessity of including the observer in the observed.

All of this is to say that the very best intellectual endeavors of humanity today are converging on the idea that “out there” and “in here” are not only inseparable, but that their mutual boundary is more dynamic, fluid, and ever-changing than a 19th Century rationality (2) would like to admit. Yet this insight is not radically new. Rather, it is new to the typeof consciousness that has forgotten or downplayed its intrinsic embeddedness in the world, a consciousness which swept the world in various forms as the “modern paradigm”; that is to say, it is new to most of current humanity.

Alchemy and the Art of Nature

It only takes a brief glance at history to see that this  insight was embodied, if not understood with the modern sense of evidence and exactness, in a variety of traditions, not the least among them that of alchemy, whose primal statement “As Above, so Below; as Below, so Above” is a wonderful expression of this wisdom. “Nature” in alchemy, had a peculiar relationship with the human being, who could, through specific processes, render it to an ennobled state. Yet the sought-for results were not made possible by external manipulation of outer substances alone. Inner substances—the feelings, passions, thoughts, and attention of the alchemist—also had to go through transformations. Moreover, it was not a simple combination or side-by-side paralleling of the inner and outer transformation that furthered the work. Rather, the inner and outer processes were inextricably entwined, mutually influencing the other’s unfolding in a rhythmic dance, as indicated symbolically by the Staff of Hermes, an important alchemical symbol.

insight was embodied, if not understood with the modern sense of evidence and exactness, in a variety of traditions, not the least among them that of alchemy, whose primal statement “As Above, so Below; as Below, so Above” is a wonderful expression of this wisdom. “Nature” in alchemy, had a peculiar relationship with the human being, who could, through specific processes, render it to an ennobled state. Yet the sought-for results were not made possible by external manipulation of outer substances alone. Inner substances—the feelings, passions, thoughts, and attention of the alchemist—also had to go through transformations. Moreover, it was not a simple combination or side-by-side paralleling of the inner and outer transformation that furthered the work. Rather, the inner and outer processes were inextricably entwined, mutually influencing the other’s unfolding in a rhythmic dance, as indicated symbolically by the Staff of Hermes, an important alchemical symbol.

The art of the alchemist was both something completely unnatural (an opus contra natura), and a way to further the already significant “art” of nature. What is important for this essay is that the entwining of the human and the natural had significance for consciousness. The alchemist’s consciousness transformed when it involved itself in the unfolding of natural processes. One of the effects of this transformation led to the alchemist’s ability to “read the signatures” of natural processes and skillfully utilize them for healing or to further the alchemical opus.

These “signatures” arise within the complex, permeable boundary between the alchemist’s inner soul life and the outer world. There is something sublime and difficult to express about this experience, because of its unique character. It is as if the substances in the outer world speak to the alchemist—not in a hallucinatory or shamanic way, but through a sensitization of the alchemist’s soul life, into which the world speaks its movements and changes as a kind of dialogue. This speaking takes shape in the alchemist’s soul life in the form of qualitative experiences of gesture, mood, and tone. These words are commonly used in situations where a human being, viewing an artistic work, attempts to ender the world of the art, and are meant here in an analogous way. Everyone already has some capacity to identify shades of meaning through an experience of gesture, mood, and tone; the alchemist (like the artist) simply develops these capacities to a much higher degree through a repeated experimentation with various processes. The development of this skill, both in the artist and the alchemist, requires a continual, closed feedback loop that connects concentrated perception of the outer world with active processes of expression (application and mixing of color in art, for example, and timing of initiation or cessation of specific alchemical process in alchemy).

But all of this was not quite made explicit, at least in a concerted or concentrated way, by the alchemists themselves. The need to abstractly and intellectually trace through from a meta-perspective the practices of their art was a form of dilettantism not cognizant of the necessary interpenetration of the art’s practice and its understanding. For this reason much of alchemical knowledge was expressed in ways that are relatively foreign to the modern intellectual consciousness, taking shape in symbolic mandalas and obtuse phraseology, deliberately or unintentionally obscuring the kind of pristine logical relations expected by a “modern mind”. On the one hand this has led to alchemy being discredited as a fanciful search for physical gold, or at best a type of proto-chemistry. On the other hand, the essential key of alchemy (in terms of the development of human consciousness as discussed briefly above) has never been lost, but has continued to evolve even into the present.

Goethe’s Contribution

A prominent figure in regards to the development of this stream is the German savant Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Goethe, who is most well known as Germany’s greatest literary figure, was inspired directly by alchemy, even going so far as to create a beautiful alchemical Rosicrucian allegory in his work The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily (Goethe, 1993). But despite his literary status as the “German Shakespeare”, his scientific works, dealing with morphology and color, are equally important, even felt by Goethe himself to be at least as significant as his other writings.

Goethe understood that the fundamental nature of the world could not be divorced from the aesthetic, and that natural processes were aesthetic expressions as much as purely physical manifestations. His morphological studies of plants and animals convinced him that each individual creature is

…a small world, existing for its own sake, by its own means. Every creature is its own reason to be. All its parts have a direct effect on one another, a relationship to one another, thereby constantly renewing the circle of life; thus we are justified in considering every animal physiologically perfect. Viewed from within, no part of the animal—as so often thought—is a useless or arbitrary product of the formative impulse. (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 121)

Goethe saw the individual plant or animal as a necessary whole, with a kind of logic of its own. Perceiving the whole meant not simply taking what was immediately available to sensory perception, and making sure nothing was left out. Rather, in order to perceive the whole (in the Goethean sense of the term), it was necessary for the human being to actively take part in the process of observation. Goethe devoted much of his life to the exploration, refinement, and application of this process, which can be called Goethean phenomenology. This methodology (for it includes many different methods for its realization, and contains a whole world-view as its basis) required that the element of time be re-introduced by the observer in a specific way. Goethe himself called this style of working a “delicate empiricism that makes itself utterly identical with the object, thereby becoming true theory. But this enhancement of our mental powers belongs to a highly evolved age” (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 307)

This is an artful empiricism, requiring a participation that aesthetically places the observer within the world of the observed through a process Goethe called exact sensorial imagination. This non-fanciful imaginative process requires the enthusiastic engagement of the feeling-life of the observer, who becomes linked with the observed in a way that, as Goethe indicates, ultimately dissolves the normally operative barrier between the observer and observed. This barrier has not always been a part of the human condition, but is a historical phenomenon, having been brought into the world with the rise of the intellectual capacity of humanity (as expressed, for example, in the consciousness of ancient Greece), and which experienced significant refinements, formalizations, and developments from the Enlightenment onward. Goethe expresses the dissolution of the subject-object boundary in this way:

…My thinking is not separate from objects; that the elements of the object, the perceptions of the object, flow into my thinking and are fully permeated by it; that my perception itself is a thinking, and my thinking a perception. (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 39)

Exact sensorial imagination requires that the human being imaginatively takes part in the unfolding of the external phenomenon. This both requires and precipitates changes in consciousness. On the one hand the task is monumentally opposed to many of the current trends in modern society, which tend towards a philosophy of “capturing” attention and “creating” intention in the briefest exchange possible (think of advertising as a whole). But if we follow Goethe, we recognize that phenomena—particularly natural phenomena—deserve our attention, and that the free giving of such attention is an act of love. In this way, the giving of attention is at the same time the focusing of intention—the intention to perceive beyond the normal habits of modern consciousness, a reaching into the unknown towards the whole. This is the equivalent of the opening up and subsequent development of a subtle inner space that is at the same time an outer space, a space that fills with both the activity of the observer and the activity of the observed in a mutually fructifying dance of becoming. We become more through the process, just as the phenomenon becomes more; both are transformed when the space between is activated and permeated with loving attention.

Reading the Signatures

Goethe practiced this art in his morphological studies of the plant world, writing many indications in his work The Metaporphosis of Plants (Goethe & Miller, 2009). An essential aspect of the process involves perception of a phenomenon as it evolves over time. The way that the phenomenon changes in response to environmental and contextual considerations (as well as its own internal complex ecology) is the important thing, not the simple fact of such changes. Examining the way a phenomenon changes is precisely what develops a soul-sensitivity to gesture, mood, and tone.

For example, it is fairly easy to identify individual people by virtue of the way they walk, independently of other identifying visual features such as body type, face, and so forth. With some training (sometimes provided in a relatively unconscious way by “life” when two people are around each other through many situations), we can even discern minute shifts in another’s walk which are indicative of subtle changes in their inner life. Their walk, as with the tone and rhythm of their voice, their breathing, and many other factors, all are avenues of expression for what is living in the individual in any complex moment. Reading the nuances of someone’s gait is the reading of their “signature”, a gateway “into” the other. The whole world is full to overflowing with these little doorways into what is at work in the process of a phenomenon’s unfolding. Following Goethe, these gateways are everywhere, as an “open secret”, and it is possible to apply oneself directly to the task of learning how to be sensitive to these qualitatively rich offerings from the world and what they have to “say”.

Something interesting happens as we build our sensitivity to the qualitative gestures of the world. A point arises where we realize that the activity of perceiving no longer bears the stamp of the “other”, impressed upon our sensation by the normally operative boundary (for modern day-waking consciousness) between the inner and the outer. What used to be “out there” now has a character of what we experience as the quality of sensations and feelings that arise “from within”. For example the arising of the feeling of hunger, or sadness, or delight, although of course having connections to outer events and processes, takes shape from within; we identify them as “ours”—my hunger, my sadness, my delight—because of the qualitative way in which the sensations arise. Following through with the Goethean methodology, it is possible to reach the point where one can experience aspects of what normally is identified as belonging strictly to the outer world inwardly, having the same qualities as sensations that we normally identify as arising from within. We thus have the experience of the sensation of the qualities of an outer process as if it were “mine”, arising from within like hunger, sadness, or delight, but bearing its own particular character, we could even say, its own language.

What is more, we may realize that the experience has something of the nature of a two-way-street: something flows back from us to the external process. We have involved ourselves in a dynamic feedback loop of a very subtle character, which spans the inner world and the outer world. In a way, it is possible to say that we connect with the inner nature of outer processes, “tuning” ourselves in a way that allows the outer world’s inner aspect to become our own inner sensation. But this process is not passive; it is dynamically active, and our tuning loops back in a delicate way into the unfolding of the whole process. Our perception becomes less like that of a passive observer standing at a distance and more like a loving activity, a gift of attention that flows outward through our intention. In a quite literal way our perceiving becomes love, and it is this love that actively unites us with the phenomenon.

Moving-Image-Building

But participating in the unfolding of a phenomenon in this way requires that we learn to perceive exactly. This involves, in part, building the capacity for an exquisite inner awareness that is capable of tracing the roots and development of what takes place in our own inner lives when the phenomenon in question is absent. This is an intense and life-long procedure, and there are no real short-cuts. One does not become a Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo in a week or month, but through years and years of repeated practice. Being able to follow the traces of the rising and falling of our feelings, emotions, sensations, thoughts, and impulses is important not because it allows us to exert greater control over these realms, but because it sensitizes consciousness to our own gestures, moods, and tones. This builds a foundational palette, like the artist’s color palette, which can mix in uncountable ways to make new, slightly variant expressions. In this sense, every Goethean observer is an observer of onself, and it is never possible, nor is it desirable, to separate oneself from the process of observing. Rather, the goal is to insert oneself in the process in a way that does the phenomenon justice, by giving it the space to speak its transformations through the language of qualities (3).

We are complex beings—wholes—and it is unreasonable to expect that we can arbitrarily separate off a few or many parts of ourselves when we enter into some observation. Even if every part of our inner lives were conscious this would be an impossible task, but given the vast amount of continually active unconscious processes at work, and the complexity and subtlety with which such processes can influence observation (4), it would be doubly dangerous to hold this as an ideal (and much of modern history has borne example after example of why this is dangerous). Goethe continually put himself “in the way” of the phenomena he observed, rather than attempting to stand off to the side (in the way most modern science does) so as to abstract oneself as much as possible from the process for fear of changing it.

Goethe knew that the human being was the most sensitive of all instruments, capable of perceiving far beyond any possible machine, and that it was thus important to tune the human instrument so that it could enter into the phenomena before it. Part of this process involved observing a specific phenomenon over time and across a wide variety of contexts. If this is done, certain features or aspects of the phenomenon stand out in the stream of its unfolding. These steps are like hooks that link our attention to the phenomenon in well-defined places and times. But we cannot, in our actual perception, have the whole phenomenon with all its steps and phases, present before us at once. As Goethe says,

If I look at the created object, inquire into its creation, and follow this process back as far as I can, I will find a series of steps. Since these are not actually seen together before me, I must visualize them in my memory so that they form a certain ideal whole. (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 75)

Goethe takes the individual moments that stand out and, rather than isolating them in order to determine the specific causes of that particular slice of the phenomenon so that it could be enhanced, mitigated, or otherwise controlled, he attempts to connect the individual slice with what surrounds it in time. Goethe thus takes two perceived moments in the unfolding of a phenomenon and imaginatively connects them through a process of inward picturing:

At first I will tend to think in terms of steps, but nature leaves no gaps, and thus, in the end, I will have to see this progression of uninterrupted activity as a whole. (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 75)

The whole is paramount, but it cannot be perceived in the same way that the separate, individual moments of a given phenomenon can. It takes a certain kind of human activity—we could say an alchemical activity, equally an artistic activity—to begin to form an inward picture that is capable of holding something of the complexity of the whole, without reducing it to its singular moments or piecemeal sensations. Goethe states that “if we want to reach a living perception of nature, we must become as living and flexible as nature herself” (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 64). This is another way of saying that our inwardly developed capacities must be capable of taking on the gesture, tone, and mood of the outer process that we are observing. But because we cannot perceive everything about a phenomenon all at once, we are forced to do an imaginative reconstruction of its unfolding. We must “fill in the gaps”—not in a fantastical way, but in a way commensurate with the whole of our contextualized observations over a longer course of time, and with the sensitization to the gestures, tones and moods of our own inner lives as a background. This is Goethe’s exact sensorial imagination, an imagination borne on the back of a detailed, loving sensation of the outer phenomenon, whether it be a rock, a flower, a hummingbird, or a person. This imaginative filling in of the gaps yields a sort of inner time-lapse movie that coherently morphs from state to state. But it is much more than an inner visual experience—rather it is filled with dynamic relations between unfolding qualities, qualities carried initially through the process of sensation, but which begin to have a life of their own, and which take on more and more significance.

Goethe knew that it was not enough to continually build up sequences of moving images. He saw that in order to allow the living whole of a phenomenon to present itself, a space had to be made for its appearance. The image-building process is like a kind of speaking; but in order to begin to perceive the whole we must learn to listen. Goethe felt something sublime and subtle working through the process of active sensation, which linked him to the activity surrounding and informing the particulars of any given moment of observation. For Goethe, the particular moment of observation could ultimately present a barrier to this higher-level of wholeness, which he called the “urphenomenon”. For this reason, Goethe recognized that it was just as important to dissolve the activity of sensation by which the particular presents itself to us, in order to allow the more subtle nature of the phenomenon to rise to the surface. Now we can let Goethe finish his thought from the previous quote:

At first I will tend to think in terms of steps, but nature leaves no gaps, and thus, in the end, I will have to see this progression of uninterrupted activity as a whole. I can do so by dissolving the particular without destroying the impression… (Goethe & Miller, 1995, p. 75)

It is the following of these subtle impressions, formed in us like traces of movement left by an object which is no longer itself perceivable, that we begin to feel towards the urphenomenon. This process cannot be short-cut. We must do the difficult work of observing, of building up an inner moving picture that connects the complex of our observations into a coherent whole, and then we must dissolve the particularity of our imaginative sequence and quiet our inner process of image-building, so that into the silent space thus created, the larger whole can speak. Obviously this process is extremely difficult to describe—as indicated before, nothing can substitute for the actual carrying out of the procedure—not just once, but rhythmically, just in the way that someone like da Vinci might sketch the same figure many many times from different angles.

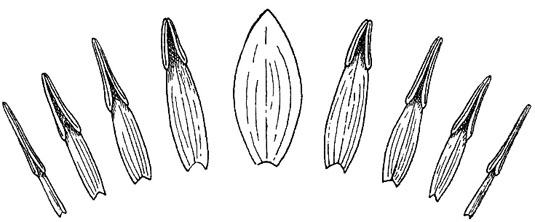

An Exercise

In order to have a place to being engaging with this process, the reader is invited to view the following still images, and then to inwardly make an attempt at morphing each leaf shape into the next. Here I have primarily focused on transformations of single leaf forms across the life cycle of a plant to keep things simple and demonstrative, but ultimately one would work with the entire plant and its surroundings. The goal is to become familiar with the specific way in which the leaf unfolds in its life cycle, and to see if one can start to feel something of its gesture, if not its mood or tone. Take the sequence forward, and then reverse the sequence and “play it back” to its beginning. At first you can do this while actually looking at the images, but the goal is to be able to reproduce the essential form without having to have the sensory object before you. Repeat this forwards/backwards process until you start to get a nice rhythm going that feels less effortful and more organic. Now for the hard part: try to dissolve the actual pictures, the visual carriers of the detail in your mental picturing, while still moving the gesture inwardly. Instead of trying to do this all at once, try to inwardly create a “soft focus”, so that the specific details of the leaves fade into the background. Let the sequence move forward and backwards while you keep a soft inward focus. With practice and familiarity with the observed phenomenon, you can begin to gain a feeling of the moving gesture of the plant, without having to be inwardly picturing a specific set of leaf shapes.

Once you have made an attempt at this, however faulty or incomplete, do the same with another sequence. You may be surprised to find that you can have a real experience of a difference in the quality of the unfolding, even if it might be hard to express in a clear thought or definitive words. See if working through all of the image sequences enhances your ability to perceive the differences in gesture between the plants. (All image credits have been placed in the endnotes to preserve an uncluttered layout.)

Figure 1. (5)

Figure 2. (6)

Figure 3. (7)

Figure 4. (8)

Figure 5. (9)

Figure 6. (10)

Figure 7. (11)

Now that you have worked on this exercise a little for yourself (you have, right?), it may be helpful to explore the following links, which lead to externalized representations (i.e. videos) of this image-building process for the sequences pictured above. These are meant only as a beginning guide for how a specific sequence of “filling in the gaps” might unfold. It must be stressed that viewing these videos will not achieve the same result as if the process is taken up inwardly, although the outer images can serve as something like training-wheels in the endeavor’s beginning. The whole point of the exercise is to actively engage with the unfolding of the sequence, not to passively view it as an object, as should be abundantly clear at this point.

(Once the image-sequences--which open in a new window--have fully loaded in your browser they will play more smoothly.)

- Buttercup

- Hairy Bittercress

- Musk Mallow

- Delphinium Astolat

- Sidalcea Malviflora

- White Water Lily

- Leaf Shapes

See how your own inner picturing is similar or different to what is shown in these “outer” videos. Whether you work with still images (already abstracted from the whole of the plant), with videos, or with the plant itself, the key is to shift the focus from an outward perception to an inward perception, based on the kind of exact sensorial imagination that Goethe developed. The reward is the slow but sure development your powers of observation, an increased sensitivity to relationships between what appear initially to be separate phenomena, and a growing intimacy with your own process of knowing.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

The alchemists of old were not in a position to be able to state in exacting language the subtleties of the connection between their outer experiments and the corresponding inner changes that fed back into their work. It was only with the flowering of the scientific consciousness that such experiences could find a proper ground on which to be a figure, but even then it took a masterful figure like Goethe to express something of these processes as they were brought together in one human being—and even his efforts were but the beginning. The next phase of the work was accomplished by Rudolf Steiner, the unclassifiable polymath who lived in Europe from 1861-1925, and who recognized that Goethe had contributed something monumentally significant with his attempts at building the foundations for a qualitative science.

Steiner saw how Goethe’s methodology was a way to begin to bridge the gap between the aesthetic and scientific experiences of the human being—not in a trivial way, but in a way that actually further developed human capacities for perception. Rudolf Steiner attempted to show how following Goethe’s indications leads to what ultimately becomes the capacity to perceive spiritually. Spiritual perception, according to Steiner, can be built on the foundations laid by Goethe’s way of seeing. This seeing is one imbued through and through with an aesthetic sense. In his direct and no-nonsense way, Steiner says it thusly:

I have often drawn attention to the fact that, if we are really to understand the world, we cannot remain at the stage of mere intellectual comprehension, but that what is intellectual must gradually change into an artistic conception of the world. (Steiner, 1970)

Steiner is speaking about a radical—although subtle—evolutionary shift in consciousness available to modern humanity, a shift towards a consciousness that can bridge the long divide between religion and science through a kind of aesthetic higher beholding. Learning to perceive the art of nature as discussed above is one way that this consciousness can be developed. Yet, as Goethe indicates, this type of consciousness is one that belongs to a highly evolved age. We have far to go to achieve this vision, which has its roots in alchemy, its further development in Goethe, and its first flowering in Steiner—but the effort is surely worth it. I leave you now with a parting message from our Mother: http://www.spiritalchemy.com/video/TimeLapse.mp4

Endnotes

1: (Back) See, for example, Andy Clark’s book Supersizing the Mind . (Clark, 2008)

2: (Back) Arguably this period saw the height of rationalism, as significant cracks in the purely rational, reductive approach to nature (and ourselves) had become unignorable by the end of this century.

3: (Back) The distinction between quality and quantity is false; i.e. quantity (with its attendant features, measure, number, weight, and so forth) is full of quality. Mathematicians know this; there are qualitative differences between, say, pi and e, or between 0 and 1, or between the rational and irrational numbers, etc., each with their unique characteristics (gesture/tone/mood). Such differences carry qualities that are far beyond any strictly numerical difference. Between 0 and 1 lies an infinity, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

4: (Back) What we are capable of observing is very dependent upon the particular (often unconscious) sensitivities peculiar to a particular individual. Whether certain aspects of an outer phenomenon “appear” may depend upon whether a person is more situated towards proprioceptive, spatial, or aural stimulation, for example. It is really not a question of there being some “objective datum” that is either perceived or not—every “objective datum” is part of a perceiving ecology, which can have its own inner tendencies and rules. Good teachers are very aware of this fact, and create opportunities to engage multiple ways of knowing and perceiving in any given “lesson”.

5: (Back) Colquhoun & Ewald (1996) - Musk Mallow

6: (Back) Talbott (2009) - Buttercup

7: (Back) Mandera & Meyer (1995) - Hairy Bittercress

8: (Back) Goethe (2009) p. 109 - Delphinium Astolat

9: (Back) Goethe (2009) p. 107 - Sidalcea Malviflora

10: (Back) Goethe (2009) p. 44 - Nymphaea Alba (white water lily): petal into stamen

11: (Back) Debivort (2006) - This last image shows not the leaf shape for a single plant, but the generic types of leaf shapes for plants in general. Goethe’s morphology studies led him to recognize that the urphenomenon of the plant was the leaf. This means that all aspects of the plant were like transformations of the leaf. Similarly, every plant has a morphological relationship to every other plant; the chart (and associated video) simply demonstrate that the process can be applied at many levels, and is not restricted to a single limited set of observations.

References

Clark, A. (2008). Supersizing the mind : Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Colquhoun, M., & Ewald, A. (1996). New eyes for plants : A workbook for observing and drawing plants. Lansdown, United Kingdom: Hawthorne House.

Debivort (2006). Leaf morphology disposition Retrieved 12/19, 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Leaf_morphology_disposition.png

Goethe, J. W. v. (1993). Goethe's fairy tale of the green snake and the beautiful lily (D. MacLean, Trans.). Grand Rapids: Phanes Press.

Goethe, J. W. v., & Miller, D. (1995). Scientific studies. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Goethe, J. W. v., & Miller, G. L. (2009). The metamorphosis of plants. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mandera, R., & Meyer, U. (1995). Portrait of a medicinal plant - tropaeolum majus l. - nasturtium Retrieved 12/19, 2009, from http://www.anthromed.org/Article.aspx?artpk=248

Steiner, R. (1970). Man as symphony of the creative word (J. Compton-Burnett, Trans.). London: Rudolf Steiner Press.

Talbott, S. Can we learn to think like a plant? Retrieved 12/19, 2009, from http://www.natureinstitute.org/txt/st/mqual/ch09.htm